Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Pearl gates, golden paths, and an eternity of love encompass peace beyond understanding that is associated with “Heaven.” However, a select number of people are granted the opportunity to wake up along the deep blue ocean while being surrounded by a sea of caring green scrubs. Suddenly, these residents amend their current thoughts by adding The Connecticut Hospice to their definition of “Heaven.”

After interning here for a summer, I experienced countless patients considering the Connecticut Hospice an oasis, while many of them explicitly referred to it as “Heaven.” The peace that the patients feel is contagious, and the relief on the family's faces can be seen as a patient is newly admitted into the hospice.

There is much irony in this depiction of hospice as a heavenly location. Hospice is supposed to be the final destination for a patient, and the positive emotions that are seen on the inside of these walls highlight the character of hospice care and the current problems in our pre-hospice healthcare system. As hospice is a place that one would assume is filled with anxiety and grief, it might be perplexing for one to hear that it is filled with love, peace, and relief.

While my experience has drawn my attention to the areas that need to be amended in terms of hospice accessibility, my experience has also drawn my attention to one distinguished aspect: Hospice is the kindest form of medicine.

A hospice patient has access to social work services, art services, and spiritual care, while their family members have access to bereavement services. Hospice care works with a patient on a holistic level to offer the patient the best experience possible. While I knew the textbook definition of the generous services provided by hospice before interning here; I did not understand its true meaning until I witnessed it.

Consider the power of music in Billy’s room for an instant. Billy was a patient with dementia who had a difficult time holding up his head and could not remember his past experiences. Billy’s room was a somber atmosphere as his family was devastated to see him in such a state. All they had left to do was hold and comfort him. One day, I heard sounds of laughter and joy coming from one of the patients’ rooms. As I approached, I could hear Billy start to hum a familiar tune and gradually lift his head to look his family members in the eye. The cheeks of those around him began to glisten, but being distinctly different than before, these were tears of happiness. Feeling a smile invade my lips, Billy’s room showed me the generosity of hospice care.

In addition, consider John. While unconscious, he had countless family and friends at his bedside telling stories of his life, including generations of family gatherings at their pool. One afternoon, I visited his bedside with the director of social work, who asked the family if he would like to see a priest. The family was content with this offer and knew that this was what John would want. A few hours later, as I was getting ready to leave work, a nurse confronted me and told me that right after the priest came and anointed John, he passed. This depiction made it undeniable that this event gave John the peace he longed for. This type of story is not unique, as countless patients wait for their families to visit and for spiritual comfort before they let go. Hospice has the privilege of facilitating these generous and comforting experiences of peace for these patients.

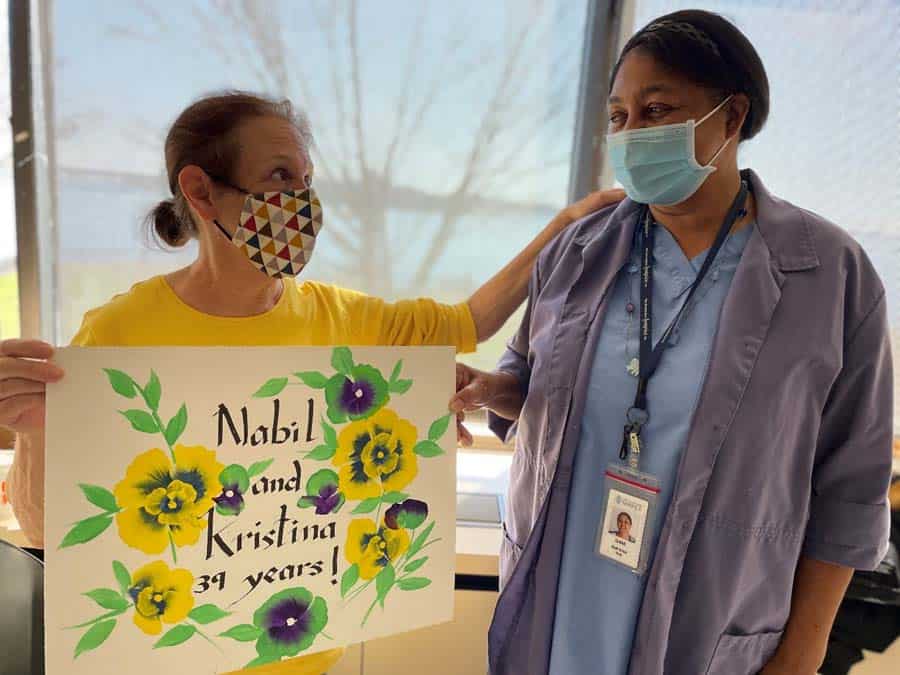

Lastly, consider Mary. Mary was one of the sweetest patients I have met, and she was diagnosed with a severely contagious disease. For this reason, she was not allowed to see her dog to mitigate the spread of her disease. The hospice nurses constantly watched her condition in hopes of letting her dog, Rover come in to visit. After a few days of Mary asking to see her dog, the medical staff deemed her clear to see Rover. The smile that overtook Mary’s face, along with the laughter that escaped when the staff told her she could see Rover was comparable to that of one reunited with a best friend. On the first day of the visit, Rover curled up on the bed with Mary as Mary brushed her hair. After Rover visited a few times, Mary’s spirits lifted, and her demeanor changed as she had a joke readily available every time I visited her. The bond that the two held was undoubtedly special, as her dog made her complete. Rover’s visit then became so routine that the doctors had it in their calendar so they may say hi. Rover became part of the hospice family.

A trend that I noticed is that when one is living the last few days of life, they crave to see their pets. The relief one feels while in hospice allows them to visit with their pets and do other activities that they might not be able to do in other forms of medical treatment, such as visit their horse, spend time with their dog, graduate from college, and spend quality time with their family members free of pain. Again, while I entered the hospice on my first day at work, I knew that special circumstances can be applied to hospice care, but I was not touched by these compassionate experiences until I witnessed them firsthand.

Growing close to patients like Mary, Billy, and John and witnessing their experiences is a special dynamic that I cherished while working here over the summer. These relationships were unique as patients would offer end-of-life wisdom that others only have an opportunity to receive once in their life from a grandparent. How fortunate was I to receive this type of advice daily?

However, the reality about these relationships is that they have an early expiration date. This aspect of the patient interaction helped me to cherish every moment that I was granted with a patient. Presenting itself as an emotionally taxing and rewarding experience, I realized that the hospice staff constantly encounters these emotions throughout their career. I soon learned the attributes that one must have to show undevoted care to each patient at a hospice, and I gained a newfound appreciation for the hospice staff.

I have learned that the staff that decides to go into hospice care have distinct reasons to enter this medical field. Many of the staff remark on living through a loved one’s passing and how a hospice made the passing a beautiful sight rather than a tragic event. However, regardless of one’s reason to go into the hospice field, it requires someone with strength, perseverance, courage, kindness, compassion, intelligence, and grace to care for someone during their passing and continue after witnessing a patient's passing.

As I write this blog, I come under the impression that you may have preconceived notions about what hospice care is, but I hope that you are touched by these experiences as if you had witnessed them yourself. I hope that you understand how hospice care stands apart from all other types of medicine in its holistic approach, its generosity, and its staff. As hospice care is invaluable, general in-patient care is also not easily attainable. In-patient care is expensive due to the skilled nursing, medications, room and board, and other services offered. Medicare will cover in-patient care stay costs; however, it can only be applied under specific circumstances. These circumstances are strict, and they leave many patients without the opportunity to experience hospice care. In addition, those who are homeless and only eligible for routine hospice care have no safe place to receive this care. Therefore, while I have been given the opportunity to understand the kindness of hospice care, I also take up a burden of desire to see in-patient hospice care become more accessible for all populations, and I hope that you take up this burden as well.

Compassion, generosity, and caring staff embody the kindness that hospice has to offer to those willing to accept. These are the aspects that I would want someone to understand and see when apprehensive about hospice care being right for them or when someone is first entering into hospice care. I would also like to highlight these aspects to those who are in a position to change the current governmental dynamics that surround hospice accessibility.

As I pass through the pearly gates surrounding The Connecticut Hospice and embark on my journey back into reality on my last day of work, I am wistful. I am filled with a sense of peace. I am grateful to have experienced such a beautiful form of medicine and a caring climate. I am content that the patients whom I have grown to care for and the ones to come in hereafter are in the hands of the kindest form of medicine.

No matter your age or health status, a properly executed Advance Directive is essential to assure you receive healthcare that aligns with your beliefs and wishes. Even the young and healthy may find themselves in an unanticipated medical situation in which an Advance Directive is critical.

An Advance Directive is a legal document that allows you to maintain control over the healthcare you receive should you be in a circumstance where you are unable to communicate your wishes to your healthcare providers.

Which Advance Directive to choose depends on your wishes, your understanding of the limitations of each type of Advance Directive, and your state of health. First, let’s review the healthcare representative. Before we do, though, some confusion about this form of Advance Directive needs to be cleared up. In addition to the term “healthcare representative,” you may also hear the phrases “healthcare agent,” and “durable power of attorney for healthcare.” Each of these is essentially the same, and Connecticut officially replaced the latter two terms with the former on October 1, 2006. In keeping with this, I will use “healthcare representative” going forward to refer to this form of Advance Directive.

A healthcare representative is legally designated by an individual to make their healthcare decisions should they no longer be able to communicate — for example, they are unconscious and cannot talk or write. In contrast to the other types of Advance Directive, a healthcare representative offers the most flexibility in directing doctors and other healthcare workers no matter the now-incapacitated person’s medical circumstance. A Living Will cannot be honored unless specific criteria are met and may not allow medical providers reasonable flexibility in the care they provide (discussed below). A Connecticut MOLST is also very specific, and is only legally used for people with serious illness (also discussed below).

Designating a healthcare representative is easy and does not require a lawyer or Notary Public. Your healthcare representative should be a person — many people designate a good friend -- who will follow your wishes for care with a lesser likelihood of being so emotionally involved as to find it difficult to do as you have instructed – such as a wrenching decision to discontinue life support. This is one reason why a friend may be a better healthcare representative than a close – and more emotionally involved -- family member such as a spouse, parent, or child.

Once you have decided who to designate as your healthcare representative – and once they have agreed to take on this important role (an alternate representative may also be designated should your primary representative be unavailable or decline to make decisions), it is imperative to have a conversation with them about what your wishes would be in a variety of circumstances. For example, some people may want more aggressive care should they become ill with a life-threatening though potentially curable illness than they would if they had a terminal illness with few treatment options and a lesser likelihood of recovery. However, it is impossible to anticipate all medical eventualities— I have tried— and one advantage of the healthcare representative is that he or she has freer rein to direct care in the spirit of your wishes – regardless of your exact medical circumstance -- than is allowed by a living will or MOLST.

To complete your legally enforceable healthcare representative paperwork, which requires two witnesses but again does not require a lawyer or a Notary Public, download a detailed PDF outlining Advance Directive procedure in Connecticut (including healthcare representative, Conservator of the Person, living will, and anatomic donations. MOLST cannot be completed with an online form – see below).

It is worth noting that you must be able to understand the consequences of your decisions to designate a healthcare representative. People who are significantly cognitively impaired, from dementia, for example, and are unable to direct a healthcare representative sensibly and reasonably, are not eligible. Likewise, someone with impaired consciousness is also not eligible. This is why it is important to choose one before becoming seriously ill.

For the sake of completeness, if you designated a durable power of attorney for healthcare in Connecticut before October 1, 2006, that person has the same medical decision-making rights as a healthcare representative. If you designated a healthcare agent – not a representative -- prior to October 1, 2006, that person may only make decisions about withdrawing or withholding life support, not all healthcare decisions. And if you don’t have a legal Advance Directive in Connecticut, healthcare providers will look to your next of kin for decisions. In order of preference, these are your spouse, adult child, and parent -- or other relatives if they are not available.

All in all, and especially considering the difficulty healthcare providers will have following instructions if family members disagree about the care you should receive, these factors make it clear that it makes far more sense to simply designate an up-to-date healthcare representative and to do it now.

A Connecticut “Conservator of the Person” is an individual, often a lawyer, appointed by a Probate Court and responsible for healthcare decisions for someone who is permanently unable to care for, and communicate their healthcare decisions – such as someone with dementia. Usually, Conservators are assigned to people who have not designated a healthcare representative and are no longer capable of doing so. While a Conservator is empowered to make all healthcare decisions, their role usually relates to custodial needs— such as admission to a nursing home— although they may also make decisions about specific medical interventions. If someone with a court-appointed conservator already has healthcare representative, having designated one while they were still able, the decisions of the healthcare representative about day-to-day medical care have more authority than those of the Conservator, unless the Probate Court disagrees.

These instructions require no further input from you, a healthcare representative, a Conservator, or anyone else to be followed by healthcare providers. The Connecticut Living Will provides instructions about your wishes regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation—or CPR — mechanical ventilation (such as a respirator), artificial nutrition and hydration, (such as tube feeding), and any other specific medical requests you may choose (such as intravenous antibiotics). The Living Will, however, is very specific as to the medical circumstances in which healthcare providers can follow its directives. These include suffering from a terminal illness, permanent unconsciousness, permanent coma, or persistent vegetative state. One potential problem with the Living Will is that reasonable people may disagree on the definition of these entities. One medical provider may believe a condition is terminal, while another may feel that there are still medical treatment options. Likewise, there may be disagreement as to whether a state of unconsciousness or coma is permanent, and how exactly to define “persistent vegetative state.” Recent research in people believed to have no conscious awareness of their surroundings— part of the definition of persistent vegetative state— has shown that some patients may have more awareness than others. This may complicate matters should there be disagreement as to whether you are in persistent vegetative state. I have seen more than one situation in which it was clear that a grievously ill patient would have wanted to be taken off life support but the wording of their living will tied the hands of their healthcare providers. A healthcare representative, on the other hand, can make decisions regardless of these uncertainties, although they should not stray too broadly from your expressed wishes. For example, someone might instruct their healthcare representative to decline further medical interventions – or to stop life support -- should the likelihood of their being indefinitely and seriously neurologically impaired be high, regardless of whether they are terminally ill, “permanently” unconscious, or suffering what may or may not be persistent vegetative state. This decision is up to each individual, and is important to convey to a healthcare representative.

Technically, MOLST is not an Advanced Directive because it specifies the medical treatment that is desired at the time the form is complete, not at some imaginary future time under some unknown medical circumstance. MOLST requires the presence of an “end stage, serious, life limiting illness” or an “advanced chronic progressive frailty condition,” is usually completed by people at significant risk of hospitalization with the risk of death in the very near future, and is very specific as to desired interventions, such as different kinds of ventilator support, ICU care, IV fluid and nutrition, and others. MOLST requires the signature of and counseling by a MOLST trained and certified physician, advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), or physician assistant, and the original lime-green form must be presented for it to be valid. More information about MOLST.

Again, a valid MOLST requires you be counseled by a trained and certified MD, DO, APRN, or PA, and have a signed, original lime green MOLST form. Counseling is imperative -- I have more than once seen incorrectly completed MOLST forms – requesting, for example, both comfort-measures only and life support – unnecessarily complicate care.

The bottom line? At the very minimum, if you are able to read and understand this blog, get to work on designating your legal healthcare representative right now.

Our 52-bed inpatient facility on the waterfront in Branford is perhaps the most distinctive feature of The Connecticut Hospice, Inc. This facility affords gorgeous views of Branford Harbor and Long Island Sound, giving our patients and their families access to an outdoor space without compare - barbeques and picnics around patients’ beds with multiple family members and friends in attendance are a common summer sight (once, a patient’s horse even came to visit).

Our inpatient hospice facility also provides the kind of up-to-date symptom management techniques that typically cannot be provided in the home setting. This includes injected pain medications, IV fluids, and other “hospital-like” procedures provided to improve quality-of-life in people with terminal and life-threatening illness. (Note - such interventions are not provided to prolong life. For example, we would not provide IV fluid to an unconscious patient who is very close to the death.)

“Having to tell people they are not eligible is the worst part of my job, and I dread it.”

- Joseph Sacco - Chief Medical Officer at The Connecticut Hospice, Inc

Unsurprisingly, the lovely setting and excellent care make admission to Branford a common request, both for hospitalized people who have decided to enroll in hospice and for those in our home care program seeking a higher level of care. It is a request we wish we could grant for all – but can’t. Hopefully, this post will clarify who is and is not eligible for inpatient hospice care and help avoid disappointment among people who thought it was open to all.

This is the level of care provided for hospice patients who are at home or in a nursing home.

Respite-level care includes five days of admission to our Branford facility (many hospice organizations provide respite care in nursing homes) where care will be provided by our nurses and other staff, allowing family members to rest (some go on a quick 5-day vacation or attend to tasks they’ve had to neglect to care for their loved one).

This is 24/7 care at a patient’s bedside at home, usually provided by a nursing aide. It is only provided for a limited time – generally two days at most – at the very end of life, for patients needing intensive symptom management. Not every patient is eligible, and staff may not be available for an entire 24-hour period.

(General inpatient care, or “GIP”): Hospital-based care, with 24/7 availability of skilled nursing, 7-day/week daytime availability of an MD, DO, APRN, or PA, and 24/7 medical oversight.

Before getting into the details of eligibility for inpatient care, however, let us first make clear that these criteria are a requirement of Medicare, not of The Connecticut Hospice, Inc., and are imposed on all hospice organizations across the country. We truly wish we could provide inpatient care for all of our patients without limitation. Facing serious and terminal illness would seem qualification enough to receive the excellent care offered not only at home but in our lovely waterfront Branford hospital; unfortunately, Medicare does not agree.

The easiest way to determine whether your loved one might be eligible for inpatient care is to ask this question: Must my loved one be cared for in a hospital setting, where skilled nursing care and medical oversight is available 24/7? Or can their care feasibly be managed at home?

Remember that even people who are unconscious but restless, agitated, grimacing, crying out or showing other signs of distress can often be provided successful symptom relief with highly concentrated oral formulations of medications such as morphine or lorazepam put under the tongue, or “transdermal” medications in patch form, such as fentanyl, that do not have to be swallowed to be effective. If these medications have been tried – and Medicare often audits our records for proof that they have – and the only means of providing relief is by injected medications, this would reasonably be considered care that is not feasible at home, and inpatient care would be appropriate.

Wounds that are large and deep, those involving bone or with excessive slough (dead, discolored tissue) or that are obviously infected (I see no need to be graphic, most people are able to tell if a wound is badly infected) may be eligible for inpatient care. There is a caveat, though; wound care in the inpatient setting is not indefinite, and most wounds in hospice care patients do not improve. Once a wound care plan is in place and shown to be adequate to a patient’s needs, we will generally discharge our patient to a lesser setting, where the care will continue to be provided by our home care team in collaboration with family members, or in a nursing home.

“Delirium” is a medical condition characterized by waxing and waning level of consciousness – your loved one may be asleep one moment and climbing out of bed the next -- confusion, short term memory loss, and agitation/restlessness resulting from altered body chemistry in serious illness. It is often seen as people approach the end of life. As with other symptoms, it can sometimes be controlled with oral or under-the-tongue (“sublingual”) medicines. As with other symptoms, Medicare requires that a good faith effort be made to manage delirium at home – if this does not succeed, inpatient care may be an option.

“Sundown syndrome” is characterized by agitation, confusion, and restlessness in elders with dementia that begins when the sun goes down and it gets dark outside. Managing sundown syndrome is hit or miss – medications given at home that work for one elder (such as a sedative like lorazepam – which can sometimes cause a paradoxical increase in agitation -- or an antipsychotic medication like haloperidol or quetiapine) may not help with another. As with delirium, sundown syndrome that cannot be managed at home may be a reason for inpatient admission.

It is understandable that family members of a very sick loved one who have been providing care 24/7 become exhausted and need a break. Unfortunately, this does not qualify their loved one for inpatient admission. The good news, however, is that they will likely be eligible for respite level of care. Generally speaking, patients receiving respite care are relatively stable – which is not to say they do not have a serious illness – take their usual meds, are able to eat, do not need injected medications, and are discharged home after 5 days

It is understandable that family members of a very sick loved one who have been providing care 24/7 become exhausted and need a break. Unfortunately, this does not qualify their loved one for inpatient admission. The good news, however, is that they will likely be eligible for respite care.

Generally speaking, patients receiving respite care are relatively stable – which is not to say they do not have a serious illness – take their usual meds, are able to eat, do not need injected medications, and are discharged home after 5 days

You may be shocked to learn that imminent death – death expected in hours or days – is not a qualification for inpatient admission, most people are. Medicare insists, however, that the criteria outlined above must be met – for example, symptoms of pain or shortness of breath require injected medications for relief – to admit a patient who is at the very end of life. Most patients in hospice die at home. The good news is that our home care nurses are available 24/7 to help families caring for dying patients at home.

You may also find A Compliance Guide to Inpatient Hospice Care provided by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) to be helpful.

You have just been diagnosed with a serious illness and your doctor is doing their best to provide you the information you need to proceed with treatment. You are terrified, overwhelmed and have no idea how to proceed. You feel like you are living out a nightmare.

Robin Kanarek was in the same situation with her husband, Joe, when their ten-year-old son, David, was diagnosed with leukemia in 1995. Robin, though, was an R.N. with over fifteen years of nursing care experience and had the medical connections and background to navigate her son's care. But as David was ready to start high school at the age of fourteen, he relapsed, and it was discovered that his leukemia was more aggressive than his original diagnosis. As he was too weak for another two-year round of chemotherapy, the Kanareks could not find a perfect match for a bone marrow transplant for David; his only chance for survival was a stem cell transplant using his then ten-year-old sister, Sarah as a donor.

Robin and her family navigated two top health centers caring for David for almost five years. David's journey ended in despair when he died in 2000 following devastating complications from his transplant. He was fifteen years old, but their journey continued; and in the midst of their profound grief, the Kanareks attempted to make sense of what had happened to heal and keep their family intact. Their grief was so insurmountable that the Kanareks decided they needed to move abroad to heal privately and focus on helping their daughter adjust to the loss of her beloved brother, become an only child, and living in a new country, and making new friends.

It was in London that Robin started her journey to heal and give her family's life some semblance of normalcy. Two years of intense grief counseling helped her realize that she could share what she had learned from her devastating experience with her son's illness. Soon she began volunteering and fundraising for a U.K. organization that cared for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Robin realized that little attention had been given to the psychological, social or spiritual aspects of care for David or themselves. She soon learned about a subspecialty in 2006—palliative care.

Most people, including health care providers, are unaware of palliative care's many benefits. Many equate palliative care with hospice, but it is not. Palliative care can be introduced at any time of a serious diagnosis and in conjunction with curative treatment, which hospice does not provide. Palliative care is ideally provided by an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, pharmacists, and allied health providers working together to address pain management, education, and medical, emotional, spiritual, and psychological support. Improving the quality of life for those who suffer from a serious or life-threatening illness is the key tenet of palliative care.

In an effort to help other families with the unique and challenging needs of cancer treatment, Robin wrote her first book, Living Well with a Serious Illness: A Guide to Palliative Care for Mind, Body, and Spirit. The topic of this book is timely. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of individuals over 65 has surpassed those under the age of five. Never before have there been so many people over the age of fifty, the age when, statistically, the greatest incidence of serious and life-threatening diagnoses begins. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), six in ten adults in the U.S. have a chronic disease (four in ten adults have two chronic diseases). These numbers point to a growing need for palliative care, particularly as modern medicine offers more aggressive treatment options for the seriously ill.

The public needs to be educated on the benefits of palliative care. Healthcare providers also require clarification on what palliative care encompasses. Unfortunately, there has been very little written in easy-to-understand language to educate the average consumer; most books on palliative care are textbooks geared toward healthcare professionals. There is a national conversation about recognizing the limits of current medicine and the importance of seeing "patients" as individuals who need and benefit from the care of mind, body, and spirit. That philosophy is the essence of palliative care.

Robin Bennett Kanarek, RN, is the president of the Kanarek Family Foundation, established in 2006, whose mission is to improve the quality of life for those affected by serious, life-threatening conditions through promoting, integrating, and educating the medical industry and the public about palliative and supportive care in all areas of health care. She lives in Greenwich, Connecticut. Her first book, Living Well with a Serious Illness: A Guide to Palliative Care for Mind, Body, and Spirit, is published by Johns Hopkins University Press. It can be purchased on Amazon.

Ms. Kanarek has performed a great service for all of us in the palliative care field. She has managed to write a book that explains, in layman's terms, what everyone should understand about the uses and benefits of palliative care. Even medical professionals will benefit from her discussions of how patients, their families, and their caregivers should be interacting when someone has a serious illness. This book should be on every bookshelf, to be read and reread as the need arises.

―Barbara Pearce, President and CEO, The Connecticut Hospice, Branford, CT

This book is a gift to both clinicians and patients. Robin shared her story from the perspective of a healthcare giver, a wife, and a mother. She speaks to the heart of how the patient and entire family is affected in the face of serious illness. The gift is in the sharing and learning we can all do to ensure David and the Kanarek family's gift of their most private and painful moments will contribute to our better journey.

―Diane P. Kelly, President, Greenwich Hospital; EVP, Yale New Haven Health

This book is essential reading for anyone who will live with a serious illness or care for someone with one―which is essentially everyone. Kanarek writes as a mother who shares the loss of her son and has spent three decades sharing her experience with others to support their journeys. It is a book written from the heart and is both a practical guide as well as a deep reflection of how to navigate the challenging, and sacred, time of the end of life.

―Betty Ferrell, PhD, FAAN, FPCN, CHPN, Professor, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, CA

Robin Kanarek is the ideal translator of palliative care for people living in the real world. She is a nurse and knows our health care system. She cared for her own seriously ill child. If someone you love is sick, this book is your guide to the oasis that is palliative care, often hidden in plain sight, but yours for the asking.

―Diane E. Meier, MD, Center to Advance Palliative Care, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City

Many articles have been written recently about the extraordinary life of President Jimmy Carter. He has been praised for having the richest post-presidential life of any former President, although there is certainly a lot of competition (beginning with William Howard Taft, who went on to serve as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court). No one can deny, however, that Carter has done a great deal for humanity in his “golden” years. He even won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

At 98, he has outlived every other former President, and is clearly an outlier in longevity, as in so many other areas of his life. For the past six or seven years, he has been battling metastasized melanoma. With lesions even on his brain, he appears from a distance to have continued to have a somewhat normal life. Now, given his condition and his advanced age, he has chosen to end treatment, and enter hospice care at home.

As he has in other ways, he is teaching us much about how to end a long and full life. Those of us who are in the hospice field hope that he lives for many months, since one of our major challenges remains getting people into hospice care in time to reap its benefits. We hope that he is accessing social work, pastoral care, equipment, and palliative treatment.

It is likely that anyone his age would meet the basic requirements for entering hospice care. All that is necessary is a doctor’s referral, citing at least one condition that, left untreated, could result in death within a six-month period. At 98, who would question that? In addition, providers look to assess the needs of patients by considering whether they have problems with, or require assistance with, ADL (Activities of Daily Living). It seems likely again, given that he is so old, that he would need help with at least some regular tasks.

While palliative care is provided for the relief of symptoms, it has a very different aim than curative treatment. It is intended to make the patient comfortable. Not all nonagenarians have pain, but the majority probably have some arthritis, stiffness, or just aches and pains. They could have trouble swallowing, have a level of memory loss or dementia, or suffer from lasting effects of past medical treatment. Making someone’s remaining time more comfortable is a primary goal for hospice workers.

Jimmy Carter’s deep Christian faith has been well documented. Even he, though, is now going through a new experience. Whether he has concerns for himself, for his 95-year-old wife, Rosalyn, or for other relatives, there may well be issues of closure or unfinished business. Pastoral care professionals and social workers are included on a hospice team, and they begin by assessing risks of bereavement for those who will survive, as well as by determining what support would be useful for the patient him/herself. These staff members also assist with the practical aspects of the dying process-funeral arrangements, paperwork, financial questions, and other issues of concern. Although we can all marvel at the length of his life, that often does not diminish the grief felt by the family, or ensure that all necessary steps have been successfully completed.

If the Carters are fortunate, their hospice will offer arts therapy and support, including home visits. While this is not a condition of participation for Medicare reimbursement to a hospice, it is a wonderful additional service that many of us fundraise to be able to offer. Music can often unlock memories and even speech in patients who have stopped talking, and arts therapists can help all members of a family to express their feelings with concrete objects or drawings. Our hospice even has an artist who provides portraits of the patient, at the request of families. These are often used at memorial services, and can serve as beloved mementos.

We often have spouses, in particular, say that they “breathed a sigh of relief” when the hospice team took over, and they could feel supported and freed from worry. People in the home, when hospice care is given there, are given instruction on the use of “comfort packs”, which are left in case of increased pain or new symptoms that arise between nursing visits, as well as on other equipment and safety procedures. They are also given a number to call, at any time of the day or night, instead of 911, if they have chosen DNR status. Rather than be taken by ambulance to the hospital, they can be talked through issues or questions by a member of the hospice team. After the patient has passed, the family can immediately reach out to hospice, who will come and do the legal death pronouncement, so that the body can be removed. While there is no required timetable for any of this, the family can count on its hospice to be there for them.

We wish for President Carter and his family the peace and joy that can come with a period of reflection, togetherness, and letting go. Hospice staff members often comment that it is a privilege to spend time with those who are dying, and that there is often more joy than sorrow, made more likely by the absence of pain or the effects of treatment. In addition to his years of national and charitable service, we are grateful to him for bringing attention to the benefits of hospice care. He is once again leading by example, and we will all be better for it.

USA Today: Jimmy Carter is in hospice care. Explaining the end-of-life care over 1 million Americans choose.

New York Times: How to Choose a Hospice

New York Times: How Does Hospice Care Work?

One of the most common questions encountered by Connecticut Hospice staff from concerned family members of patients is whether their loved one will be provided with IV fluids if they cannot eat or drink, or if they should have had a feeding tube placed. The family members of patients with feeding tubes are often uncertain about whether formula feeds should be continued.

These are excellent concerns – and understandable. If a patient is no longer able to eat solid foods or drink fluids, it would seem logical that IV fluids would benefit them, that a feeding tube might be in order, or that a preexisting feeding tube should remain in use. The answers to these concerns depend on two more questions. One, why are they no longer able to take food or fluids by mouth? Two, if they are no longer able to eat or drink, what is their quality of life?

Many hospital patients are told that they are at risk of inhaling particles of food and fluid while eating and drinking. This kind of difficulty with swallowing is called dysphagia, a lack of coordination of the muscles that allow us to swallow, and it is very common, especially in elders and even more so in elders with dementia. Inhaling food or fluid, called aspiration, can lead to serious problems, including choking and a form of pneumonia called aspiration pneumonia. A test called FEES, fiberoptic evaluation of swallowing, is used to assess swallowing. In this procedure, a thin endoscopy catheter is threaded into the nose and down to the back of the throat, or pharynx, where the and epiglottis, the little thumb like projection at the top of the windpipe, or trachea, can be observed directly. Once in place, the patient is asked to swallow a bolus of food or fluid. Normally, the epiglottis closes and covers the entrance to the trachea when we swallow. If closure is incomplete, or mistimed, food and fluid can get into the windpipe – aspiration -- and cause the problems described above. When this is observed during a FEES test, doctors describe the patient as having “failed” the swallow evaluation – an unfortunate turn of phrase. Even, worse, when dysphagia and the risk of aspiration is diagnosed, patients may be told they cannot eat for fear of the complications. In the interim, they may have a tube inserted into their nose and pushed into their stomach, an NG tube, to be used for feeding, or even undergo placement of a feeding tube directly through the wall of the abdomen into the stomach.

For some, this is fine. The victim of a stroke, for example, may have a very high risk of serious aspiration with its related complications, as well as significant neurologic impairment such as one-sided paralysis, but still have a good quality of life, and would be an excellent candidate for a feeding tube to provide the nutrition and water necessary to stay alive. I have known people with stroke who were fed by feeding tube continue to enjoy life for years. An elder with advanced dementia, on the other hand, with a very poor quality of life – bedbound, little conscious understanding or enjoyment of life – would not be a good candidate, at least from the medical perspective. In fact, counterintuitive as it seems, feeding tubes, or “PEGS” (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes) have been shown to cause more harm than good in elders with advanced dementia, leading to bedsores from increased production of urine and stool, swelling and breakdown of skin, and even pneumonia due to aspiration – the very problem they are intended to solve. Even though the patient is no longer being fed food or drink by mouth, PEG tubes do little to prevent aspiration. Sometimes this is because people continue to produce saliva, and this is inhaled. Overfeeding or weakness in the valve that separates the stomach and esophagus – swallowing tube -- may be another cause of aspiration when formula trickles up the esophagus and into the trachea past a non-functioning epiglottis.

The decision to place a feeding tube in someone with advanced dementia, however, is a personal one. It should always be based on the individual’s wishes – which hopefully have been discussed before dementia made the conversation impossible -- and may be influenced by many factors, including religious beliefs. If those wishes are not known, however, a decision based on their best medical interest would be to not place a tube. See below for discussion of options to provide food and fluid by IV in dementia.

What to do? First, it is important to recognize that aspiration is common, especially in elders, including those without dementia. And while it is almost too obvious to be said, the ability to enjoy the flavors and smells of food and drink is central to enjoying life – making the decision to place a feeding tube a very serious one. Why would anyone want to give up eating a great meal as life’s end approaches? Second, the consistency of food and fluid, and how it is eaten. can do a lot to help prevent aspiration. Pureed food is safer to eat and less likely to cause aspiration than more substantive forms of solid food, like chucks of meat or potato, and fluid thickened (usually with corn starch) to the consistency of maple syrup, called nectar-thick, is safer than regular “thin” fluids. Both make swallowing a slower and more easily controlled process and reduce – though not eliminate – the risk of aspiration.

In hospice, we offer food and fluid to everyone who wants and is able to eat and drink, regardless of risk of aspiration, so long as they understand and consent to the associated risks. Our nursing attendants are patient and skilled. Elders with dementia and risk of aspiration are fed while sitting upright – who eats while lying down?? – in small quantities – spoonfuls or even half spoonfuls at a time. Usually, though not always, aspiration is minimized or eliminated – and the food is enjoyed.

But what of people who are unable to eat or drink at all – in whom the problem is not aspiration, but a complete inability to swallow or hold food in the stomach?

Some of our patients have bowel obstruction, blockage of the intestine or stomach. This is most commonly due to advanced gastrointestinal or gynecologic malignancies, but can also be a complication of prior abdominal surgeries (the latter patients can sometimes have the obstruction relieved with more surgery). These patients can swallow just fine, but the food has nowhere to go once swallowed and is vomited back up again, sometimes violently. In cases like this, where surgery cannot reverse the blockage, a so-called venting gastrostomy can help. This fancy sounding procedure is quite simple. A tube, like a PEG tube, is inserted through the abdominal wall into the stomach, except now, instead of being used to put food into the stomach, it is used to drain food out of the stomach. People can enjoy the smells and favor of food and chewing and swallowing. The food and fluid they eat is simply drained out of the stomach through the tube after it is swallowed. I have more than once seen someone drink a cup of bright red cranberry juice and watched it come right back out through the tube seconds later. Once, a patient with a bowel obstruction told me her last wish was to eat raw oysters and vodka. I recommended a venting gastrostomy. A week later, we ate raw oysters and drank vodka together – after hours, of course.

And what of the nutritional and water requirements of people who can’t eat or drink – or whose food and fluid does not make it past their stomachs?

This is where the second question becomes important. What is the patient’s quality of life? The patient with a bowel obstruction who ate oysters and drank vodka was wide awake, fully aware of her situation, and lived life as fully as she could – visiting with friends and family, walking walks, enjoying media and books, much like everyone else. In her case, the provision not only of IV fluids, but complete intravenous nutrition was appropriate both medically and ethically. She had a PICC line - or peripherally-inserted central catheter, a type of long lasting IV – and was provided IV nutrition, called TPN or total parenteral nutrition, allowing her to stay alive and even relatively well for months. When her disease got worse, as the cancer that had spread through her body progressed, and as the quality of her life declined, the use of TPN became less helpful. She soon needed opioid analgesics for pain and sedatives for restlessness and drifted into unconsciousness. At this point, TPN became a liability, causing problems with increased volume of stool and urine, and associated increased bedside care needs that worsened her agitation, and a lot of saliva, causing coughing and choking. Now, there was no medically sound indication for IV fluid or TPN, and it was stopped – in keeping with her wishes and those of her family. She died peacefully soon after.

The decision to provide intravenous nutrition and water to people with advanced dementia, on the other hand, is trickier. As was described in the discussion about feeding tubes, the quality of life in very advanced dementia is often poor – although this assessment is entirely subjective. The unfortunate patient with advanced dementia is bed bound, unable to eat, at such high risk of aspiration as to making eating impossible, completely dependent on others for cleaning and toileting, and profoundly cognitively impaired – unable to speak or understand spoken words, alive by virtue largely of having a pulse, blood pressure, and spontaneous respirations. IV fluid or TPN will keep a demented elder alive, as just defined, but the qualities usually associated with enjoying life, which may be as minimal as being just aware enough of and able to communicate in some way with loved ones, are entirely absent. To subject someone confronted by that horrific dilemma to IV fluid, and associated bedsores, swelling, increased secretions of saliva and aspiration, pneumonia, and repeated hospitalizations, is not a decision to be taken lightly and, in hospice, we recommend against it.

We hope this has been helpful. Keep your eye on the Connecticut Hospice blog for more information on topics relevant to people with advanced illness and their loved ones.

Further reading: Nutrition Concerns for Terminal Patients

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.