Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Dementia is a group of irreversible illnesses that progressively rob people of the ability to remember, think, speak, walk, or care for themselves, ultimately rendering them bedbound, mute, and incontinent before taking their lives. Caused by degeneration and loss of brain tissue, dementia is among the most dehumanizing of the many diseases seen by hospice workers, attacking the cognitive functions that make us unique – funny, loving, accomplished, smart, kind -- and able to manage our day to day lives at work, home, transportation, dining, socializing.., everything.

Alzheimer’s Disease is a neuropathologic disease of the brain; Alzheimer’s Dementia is the resulting clinical syndrome. Alzheimer’s Dementia is most common form of dementia in the United States, accounting for 60–80% of cases. In 2024, it affected approximately 6.9 million adults aged 65 and older, with 13.8 million cases expected by 2065. It is characterized by the insidious onset of cognitive impairment, most commonly subtle memory loss, especially the ability to retain recently acquired information. Other basic cognitive skills, such as the ability to dress, bathe, name objects, and follow simple instructions are relatively spared in the early stages. Memory loss and cognitive impairment progress over years, ultimately causing complete physical and mental incapacitation and total dependence on others.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may precede all forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s Dementia. MCI is distinguished from early dementia by the preservation of independent daily functioning, including tasks (more complex than bathing and dressing) such as managing scheduled medications, shopping, meal preparation, and household chores, though mild difficulties occur and may be noticeable to others. MCI may also include problems with semantic memory (such as difficulty naming common objects in photographs or recalling the dates of well-known events), and episodic memory (recall of recent personal events or forgetting important personal information such as appointments). These impairments may be seen in isolation or in combination, may persist or resolve spontaneously, or may progress to dementia. People with isolated episodic memory impairment have the highest risk of progression to Alzheimer’s Dementia, whereas those with impaired cognition other than memory loss are more likely to progress to non-Alzheimer’s dementias such as Frontotemporal Dementia, Dementia with Lewy Bodies, or Vascular Dementia, though this association is not definitive.

Normal aging is also associated with declines in memory and cognitive functions -- a possible cause for alarm in people with an understandable fear of developing dementia. Fortunately, the deficits that come with age do not interfere with independence and daily functioning, and are not associated with the onset of dementia. Memory changes are benign and typically involve forgetfulness for names and where common objects are located (misplaced your car keys or glasses lately?); cognitive decline is likewise benign, including, for example, difficulty with tasks requiring divided attention, multitasking, or needing more time to respond to questions. Brief memory lapses in normal aging are minor, stable over time, and do not progress. Daily functioning is preserved, and deficits may only be apparent to the individual.

Interested in learning more about dementia? This blog is excerpted in part from the contribution by Joseph Sacco, MD, CMO, The Connecticut Hospice, Inc., to Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Guide for Hospice Clinicians, published by the Hospice Foundation of America, available in March 2026.

Dementia, a syndrome of progressive cognitive deficits that interfere with social and occupational functioning, results from degeneration of the brain of varying causes. The most common types include Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), vascular dementia, and Lewy Body dementia. These debilitating syndromes are becoming more common as America ages, increasingly result in hospice enrollment, and have been the subject of several past Connecticut Hospice blogs.

The drugs used to treat dementia fall into three categories: acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine), the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine, all given by mouth, and the anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies lecanemab and donanemab, given by infusion. The effectiveness of these drugs and their possible harms are the subject of this blog.

It is important to recognize that dementia is not one illness, and that different drugs have different outcomes depending on dementia type and may even vary between individuals with the same type of dementia. Donepezil and galantamine are only FDA-approved for mild to severe AD, and memantine is approved for moderate to severe AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors may show benefit in dementia with Lewy bodies and mild to moderate Parkinson’s related dementia, but only rivastigmine is FDA-approved for Parkinson’s dementia (rivastigmine is also approved for AD). Memantine may show a small benefit in moderate-to-severe vascular dementia, but, again, it is not FDA-approved for this use. There is no evidence of benefit for any of these agents in frontotemporal dementia. The anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies are only indicated and FDA-approved for patients with mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease with confirmed amyloid pathology (by PET scanning or cerebrospinal fluid testing). There is no evidence supporting their use, nor are they approved or recommended for other types of dementia. Notably, the anti-amyloid antibody lecanemab costs approximately $26,500 per year, not including the substantial additional costs of required infusions, imaging, and monitoring for adverse effects.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors should be started at the earlier stages of disease, when they have the greatest benefit. This benefit wanes over time and is minimal in advanced disease or in patients over 85 years old. Memantine should be started in moderate to severe stages. Combination therapy may be considered as dementia progresses.

The studies on these drugs report the “effect size” – the difference between the drug and placebo on outcomes such as cognitive function, overall status, activities of daily living (such as the ability of a patient to independently eat, dress, walk, bath, and groom), institutionalization, caregiver burden, and quality of life.

Overall, the literature demonstrates positive effects for all three categories of drugs when compared to placebo (with exceptions), but is not encouraging as to meaningful real world outcomes for people living with dementia. Large reviews show small though statistically significant improvements in some measures of cognition, though these are generally below the minimum considered clinically important for most patients. There was mixed evidence for delayed institutionalization, some evidence for reduced caregiver burden, but no demonstrated impact on quality of life. The slowing of cognitive decline may not be evident to individual patients or caregivers.

None of these agents have been shown to improve cognition. Rather, the clinical course for most patients is stabilization or a slower rate of cognitive decline, with no actual cognitive improvement. Cognitive decline usually resumes at the pre-treatment rate after several months of treatment.

The side effects of these agents can be significant and even life threatening, and patients using them, who are typically unable to advocate for themselves, should be closely monitored.

The most common side effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, insomnia, dizziness, headache, slow heart rate, fainting, and weight loss. These side effects are more frequent at higher doses. Agitation, depression, and appetite disorders (including poor appetite) are more common than with placebo, and may be especially problematic in people with preexisting psychiatric and behavioral complications of dementia. Slow heart rate and fainting are potentially fatal, especially in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions.

Memantine is better tolerated than acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The most common side effects are dizziness, headache, confusion, and constipation. Gastrointestinal and psychiatric side effects are less common.

The most common side effects of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies are so-called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) – a specific set of abnormalities seen only on MRI scanning -- and infusion-related reactions. ARIA is often asymptomatic but can cause symptoms such as headache, confusion, visual disturbances, dizziness, or neurologic abnormalities. Clinically significant and fatal brain bleeding have been reported. Infusion-related reactions (e.g., chills, fever, nausea, rash) are also common, typically mild to moderate, and most often occur with the first few infusions.

In summary:

Dementia is common, debilitating, and heartbreaking. The many forms of this disease, including Alzheimer's dementia (or “disease”), Lewy Body dementia, and vascular dementia, all cause cognitive impairment, memory loss, impaired functioning, and varying degrees of physical (or motor) impairment. While medication may delay the progression of dementia (depending on type) – and only modestly at best -- the disease is invariably progressive, and ultimately robs its victims of the ability to recognize loved ones, talk, get out of bed, feed or take care of themselves, and eventually causes death. The course of this terminal illness is about 7 to 10 years. Dementia is increasing in prevalence as America ages; it is estimated that more than 9 million Americans aged 65 and older could be living with dementia by 2030, and nearly 12 million by 2040.

For a more detailed description of the different types of dementia, see, Understanding Dementia Progression, Hospice Eligibility, and the Importance of the FAST Score.

The Connecticut Hospice can provide much needed information and help for the care of people with dementia. However, to be enrolled in hospice, a loved one with dementia must meet Medicare’s requirements for eligibility. Unsurprisingly, these are far from straightforward. Hopefully, this post will help you better understand them such that you can effectively advocate for your loved one and obtain hospice services.

Per Medicare, a physician must certify a prognosis of six months or less “if the terminal illness runs its normal course” for a patient to qualify for hospice. For people with dementia, such a prognosis can be established by two methods.

One is by using Medicare’s “Disease Specific” guidelines, which establish very particular criteria as to both the type of dementia a patient must suffer and its severity.

The type(s) of dementia required by Medicare are called “Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders.”

Again, Medicare is very specific. Your loved one must be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or have one of the several other possible causes of cognitive impairment (see below*). Most of these additional diagnoses are relatively rare. Fortunately, however, one, “senile degeneration of the brain, not elsewhere classified” – broadly defined as progressive decline in cognitive function, including memory and reasoning, associated with old age and not specifically due to Alzheimer's disease or other explicitly defined conditions -- provides a work around for hospice enrollment. That is, your loved one must either have Alzheimer’s dementia, one of the other less common causes of cognitive impairment, or “senile degeneration of the brain” to qualify for hospice.

Next is the severity of illness. This is where the FAST score comes in. FAST, or Functional Assessment Staging Tool, is a scale used to evaluate functional decline in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. A FAST score of 7 or greater, ranging from “a” to “f,” is required by Medicare for hospice enrollment.

A FAST score of 7 means that dementia is advanced, and the afflicted individual is unable to walk, dress, bathe, or toilet without assistance, is occasionally (or always) incontinent of bowel and bladder, and has speech limited to six or fewer words in a single utterance. A patient with FAST 7a or b may still be able to walk with assistance and eat independently, though some hospices require a score of 7c, meaning they are no longer able to walk at all.

For those with FAST 7a, Medicare also says they “should have had” one of several medical complications in the year prior to enrollment. These complications include pneumonia, kidney infections, sepsis (bacteria in the blood), severe bedsores, recurrent fever, and reduced oral intake with a 10% weight loss in the prior six months or a serum albumin (a blood test measuring body protein) of 2.5 or less.

Other conditions that contribute to eligibility include “functional status,” including level of consciousness and ability for self-care, and “co-morbid” diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, thyroid disease, and other chronic illnesses.

To summarize, you may seek hospice care for a loved one with dementia if he or she has an established diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or a “related condition,” is dependent on others for walking, dressing, bathing, and toileting, is occasionally (or always) incontinent, can only meaningfully use 6 or fewer words in a single utterance, and has suffered a complication like pneumonia in the last year, or has lost 10% or more of their body weight in the last 6 months. Eligibility is supported by increased caregiver needs, fluctuating level of consciousness, and the presence of other chronic illnesses. Some hospices may insist on a FAST score of 7c or greater (up to 7f), meaning they can no longer walk at all, in addition to the above complications.

The next Connecticut Hospice blog post will explore Medicare’s “Non-Disease Specific” guidelines for enrollment in hospice, which may offer your loved one with dementia an opportunity to receive hospice care even if the disease is not quite as advanced as described in this post.

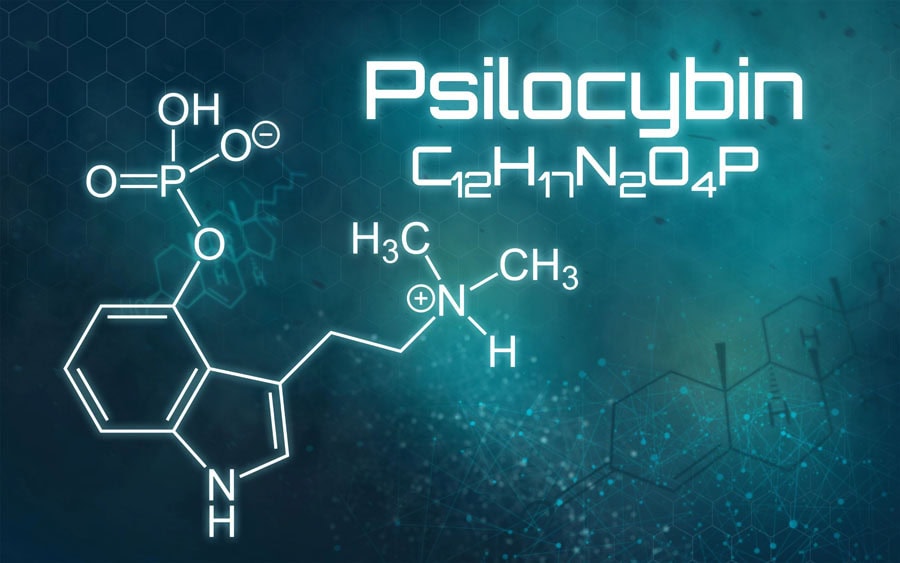

Hallucinogens, used in psychiatric practice in the 1950s and 60s for the treatment of addiction, alcoholism, depression, and other disorders, were designated as Schedule 1 – illegal – under the Controlled Substances Act in 1970.

While still federally illegal in 2025, these substances have reemerged as promising therapies for the management of a variety of psychiatric illnesses and in end of life care.

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms,” has shown positive outcomes in terminal cancer patients and those with other life-limiting conditions, particularly in patients struggling with existential distress, anxiety, and depression in advanced illness.

While beyond the scope of this blog, the basic mechanism underpinning the therapeutic benefits of hallucinogens is believed to involve the agents’ ability to increase “neural plasticity” in the brain—especially regarding long-held personal beliefs. These preexisting, “hard-wired” neural pathways (the so-called “Default Mode Network”) define an individual’s memories and plans, role and place in the world, interpersonal relationships, and other traits central to the ego, or sense of self.

People using hallucinogens often describe a dissolution of the ego, resulting in a broader sense of belonging or even merging with nature, other people, and the universe. They report a quieting of the internal narrator (“I am defined by this, my role is to do that”).

People using psilocybin at the end of life—particularly those questioning the meaning and value of their lives and fearful of ceasing to exist—may redefine death not as an ending, but as a process of transition to something eternal or interconnected.

Many also find deep spiritual meaning, regardless of religion, a sense of peace, emotional catharsis, and a belief that consciousness and love transcend death.

Several studies have been conducted using psilocybin in seriously ill patients and those at the end of life:

It is important to note that these outcomes are not guaranteed. “Ego death” can be terrifying if a person is unprepared.

Psilocybin is currently not a part of the CT Hospice formulary. However, as research in the field progresses—presumably showing salutary effects of this hallucinogen in patients at the end of life—it may become a more commonly used drug (assuming it becomes legal!) in our never-ending quest to improve end of life care.

It takes many professionals to provide the excellent care for which Connecticut Hospice is renowned. Previous blogs have recognized the critical role of nursing, arts and volunteers in patient care. This month, we are pleased to acknowledge the essential contributions of our hospice social work department.

Social work occupies a central position in the inpatient and outpatient hospice setting. Patients and families are at a critical juncture in life; emotions and the need for psychosocial care are intense. Reactions to terminal illness and impending death include fear, depression, denial, anger and anxiety. Long standing patterns of family dysfunction and the patient’s need for autonomy can further compound and complicate already complex end-of-life care issues. It is this environment of physical and emotional turmoil the social worker confronts, acting as a guiding and stabilizing force to help patients and families navigate this most difficult human experience.

The role of a hospice social worker is a multi-faceted one. At its core, it involves collaborating with other health professionals to improve quality of life, and to encourage preparedness and coping of patients and families dealing with life-limiting illnesses. This is initially achieved by completing a comprehensive psychosocial assessment, necessary to help patients and families understand care options related to their goals and life circumstances and to identify local services and resources for additional practical support.

The hospice social worker also functions as a therapist, addressing the emotional aspects of late-stage illnesses and helping patients and families come to terms with the end-of-life process. Supportive counseling helps families and patients process grief and loss, mitigates prolonged grief, and provides therapeutic emotional support for their well-being and comfort.

Finally, the hospice social worker advocates for each patient’s end-of-life wishes, recognizing the right of patients and families to self-determination. As an integral part of the interdisciplinary team, the hospice social worker provides psychosocial expertise, vitally contributing to the holistic approach to patient and family care in the hospice environment.

You will never be bored.

You will always be frustrated.

You will be surrounded by challenges.

So much to do and so little time.

You will carry immense responsibility and very little

authority.

You will step into people's lives and you will make a

difference.

Some will bless you

Some will curse you.

You will see people at their worst . . . and their best.

You will never cease to be amazed at people's capacity for

love, courage, and endurance.

You will see life begin . . . and end.

You will experience resounding triumphs and devastating

failures.

You will cry a lot.

You will laugh a lot.

Should you be interested in availing a loved one confronting the end of life with the social work, medical, nursing, arts, and other services offered by Connecticut Hospice, please call the admissions department at 203-315-8540.

In celebration of National Nurses Month, May’s blog will recognize the enormous contribution of nursing to the hospice movement – in the United States and worldwide.

The Connecticut Hospice, Inc., America’s first, was founded by Nurse Florence Wald. After earning her Masters in Nursing in 1941 and serving in the United States Signal Corp in World War Two, Florence was Dean of the Yale School of Nursing from 1959 to 1966, and became a full Professor of Nursing in 1980. Inspired by the work of Dr. Cicely Saunders, a one-time nursing student who started the modern hospice movement at St. Christopher’s Hospice in London, she founded The Connecticut Hospice in 1974, making it not only the first hospice in America, but the first hospice in the world to care for patients at home.

Fifty years later, The Connecticut Hospice remains a leader in the hospice movement in Connecticut, the United States, and around the world. The contributions of nursing, not only at Connecticut Hospice, but to hospice nationwide, cannot be overstated. Hospice care is nurse-driven, nurse-supported, and nurse-provided, whether it is delivered to patients at home, in assisted living or skilled nursing facilities, in free-standing hospices, or in hospital-based hospice.

Hospice care of unparalleled excellence is provided by the nursing staff of The Connecticut Hospice, headquartered in Branford and crossing the state from Fairfield in the west, Meriden in the north, to Essex and Westbrook in the east. Nine full-time registered nurses, two full-time licensed practical nurses, and seven full-time certified nursing assistants serve patients at home, in nursing homes, and in skilled nursing facilities, providing 24-7 availability for visits, complementing social work, volunteer, and spiritual care staff.

Additional nursing staff caring for hospice inpatients in our 52-bed licensed inpatient facility on the water in Branford includes eighteen registered nurses and eleven certified nursing assistants. Senior leadership also sees its complement of nurses, with a new RN Chief Executive Officer, and an RN Chief Operating Officer, Director of Home Care, and Director of Inpatient Nursing. Four advance-practice registered nurses serve our palliative care and GUIDE patients and provide inpatient medical care in collaboration with the physicians of the Department of Medicine. Physician staff, in contrast, consists of one full-time, and four part-time MD/DOs.

The Connecticut Hospice exemplifies the critical role and importance of nurses in American health care. Join us in celebrating them for National Nurses Month, May 2025.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.