Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Volunteers are at the heart of any hospice program. In fact, the Medicare Conditions of Participation for hospice care require that five percent of all care be given by volunteers. Why would such a regulation exist? There are many reasons.

Hospice programs are designed to treat the entire family, from the time of admission through a year after the patient’s death. No one person can fulfill all of the needs of every family member, but the presence of an active volunteer program makes it much more likely that patients and families can have their pressing needs met. Volunteers are an extension of the staff, and make it possible for a hospice to do more for everyone.

Volunteers bring talents that might not be possessed by anyone on the paid staff. Whether it be hairdressing, reiki, massage therapy, gardening, or knitting, those who come to volunteer have a variety of competencies, many of which may be apart from any professional skills. It’s not uncommon to find a retired CEO that can fix things, a teacher who does massage therapy, or a former librarian who can get office work done.

Volunteers don’t have to do the everyday tasks, so they can go above and beyond for patients and visitors. One of the most popular assignments is something called a “loving whisperer”—a person who sits by a dying patient, who has no relative present, holding a hand or giving comfort in other ways. People who like to drive, and who might bring a family member who doesn’t have a car to visit, or pick up a prescription and deliver it to a homebound patient, are like gold to a stretched paid staff.

Therapy pet owners are mobbed as soon as they come off the elevator. Everyone, including the professionals working at the hospice, are happy to pet a dog with a wagging tail. The cheer they bring is hard to duplicate with humans!

Time is often a precious gift in and of itself. Volunteers may roll beds outside on a sunny day, or even just sit and listen to stories, confessions, memories, or fears. They learn to just “be”, in a rushed world where everyone has a job to do. At the end of life, the days may be short, but the minutes and hours can be long. How much better it can be to talk to a willing listener, than to watch daytime TV! These helpers are often around at times with fewer visitors, and many have the patience to simply sit in silence, or to be a cheerful face when a patient wakes up from a nap.

Many volunteers also willingly do daily tasks that free others up. One such duty is checking visitors in at the front desk. Those cheerful souls calm and comfort anxious guests, making a huge difference just with a few kind remarks. One such volunteer noted that men, in particular, are often uncomfortable in such medical surroundings, and are gratified to be greeted and recognized as grieving relatives. Sometimes they find it easier to unburden to a stranger, and volunteers are practiced at letting them do just that.

The same holds true at the bedside, where deep feelings may be expressed. One volunteer spoke of listening to a woman over the course of her stay, vocalizing gratitude for her husband coming faithfully each day for lunch. After she passed away, the volunteer was able to communicate that gratitude to the husband, who had never heard it directly from his wife. Stories like that are not unusual, and mean so much to those left behind.

What do the volunteers get in return? Most say immediately that they receive more than they give.

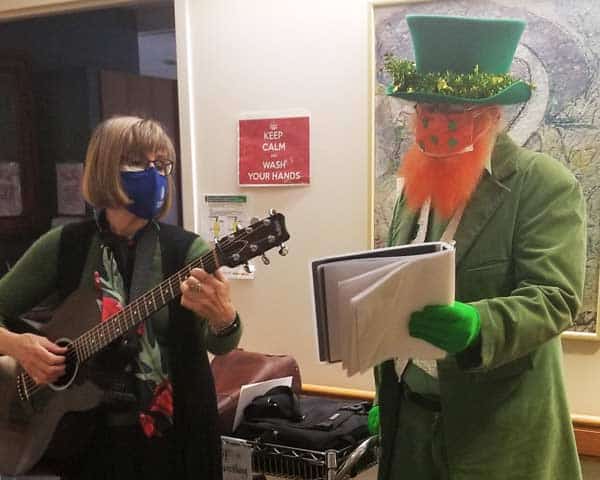

Many musicians have a day job doing something completely different, so they enjoy getting the chance to play for an audience. Families can connect within their own group, or even with other families, through music. Patients may be soothed, or even energized, as is the case with some suffering from dementia, by favorite songs. One man who hadn’t spoken in days, but who had been a competitive ballroom dancer, opened his eyes after his wife requested a specific number from those days, and asked “shall we dance?”. Moments like that keep volunteers coming back over and over.

Many are laypeople, but with an interest in spirituality of all kinds, and a desire to offer that to those requesting it. Even those without formal religious views can find solace in discussing some of life’s biggest questions with these dedicated helpers. In the vein of the old saying that the best way to learn something is to teach it, they feel enriched by experiencing the faith, and doubts, of others.

Many students, whether training for medical careers, doing community service, or just giving some extra time, find that they are amazed by everything that they learn while volunteering. Some say it was the most transformative part of their education. Others are moved to search for a career in hospice or a related field. Students who do technological projects may not be taking care of patients, but they are certainly exposed to the philosophy of palliative and hospice care. For those who are in medical, nursing, or paraprofessional schools, it may be very different than what they are taught in settings where curative care is the guiding principle.

Not only medical clearance, but fingerprinting (if working with patients), interviewing, and training are all mandated. Most hospices also ask that applicants wait a year after a personal loss to become a volunteer. Rather than considering that list to be a high hurdle, it should be seen as a compliment, to show that volunteers are just as important as employees, and should be vetted that way.

It’s easy now to see why volunteers are so critical to a hospice. Indeed, their passion for the mission is inspirational not only to patients and families, but to the paid staff as well. The staff not only acquire extra hands and minds to aid in their work, but are buoyed by the caring and support of those who show up faithfully to help, week after week. Some come daily, some weekly, and some seasonally, but all bring the reminder of the meaning of hospice care.

They all are clear on one thing: Hospice work for them is anything but depressing. They speak of it as “joyous”, gratifying, and rewarding. All value the human connections they find in those settings. In doing their important work, they find meaning. And they are grateful—for health, for life, and for every day. What more could a volunteer, or indeed anyone, ask?

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.