Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Respiratory failure -- the inability to breathe well enough to maintain life -- is a very common consequence of a broad spectrum of medical illnesses. In fact, it is the final consequence of any illness that gets bad enough to cause death; people stop breathing and their hearts stop beating. The exception are people who suffer from a heart rhythm abnormality which causes their heart to stop prior to their losing the ability to breathe. In both cases, without further medical intervention, death ensues.

For many, respiratory failure represents a natural death. For example, patients in hospice who are no longer benefiting from treatments directed to the management of their illnesses will get sicker until they eventually suffer respiratory failure. It is the hope of the hospice team that they will be able to enjoy the time that remains to them when while they are in hospice as much as possible before this eventuality.

For others, respiratory failure may happen while they are still experiencing and seeking treatment for a manageable or even curable illness. For example, someone with cancer may be benefiting from treatment directed towards its cure but still suffer pneumonia serious enough to cause respiratory failure. Without urgent respiratory support, that patient will die.

This is where intubation comes in. This straightforward process involves inserting a tube called an endotracheal tube into a patient's trachea, or windpipe, fixing it into place, and attaching it to a machine called a ventilator that will do the patient’s breathing for him or her. This keeps the patient alive while doctors treat the pneumonia – or a wide variety of other problems -- and hopefully cure it, allowing the patient to breathe on their own once again.

In some cases, patients may be treated with so-called noninvasive ventilation, meaning that rather than inserting an endotracheal tube -- or intubating -- a mask that covers the nose and mouth is strapped tightly on the patient and a combination of air and oxygen blown forcibly into the patient's lungs. Called CPAP or BiPAP, this procedure is a bit like driving a car at 60 miles an hour and putting your head out the window face first into the wind. Other people have partial respiratory failure. They can breathe on their own for a period of hours and then become exhausted, after which they are provided noninvasive ventilation to both keep them breathing and give them a rest.

Sometimes, despite being treated for the condition that caused respiratory failure, patients are not able to breathe unassisted and doctors are unable to “extubate” them -- or remove the endotracheal tube. Many such patients are wide awake and enjoying a good quality of life and elect to remain on ventilator support. The intubation tube, however, cannot be left in long term. It has a doughnut shaped balloon at the end, which is inflated after insertion to hold it in place. This causes pressure on the delicate walls of the windpipe. Over the long term, this causes damage and scarring that can dangerously narrow the windpipe. Instead, a tracheostomy is performed. In this procedure, a hole is cut into the windpipe well below the upper trachea, where scarring is most likely, and a short J-shaped tube inserted into it to be connected to the ventilator. This tube can be taken out for cleaning and replaced, improving hygiene. It even allows the placement of a speaking valve that can return the ability to speak out loud to a patient who hasn't been able to do so for a period of days or even weeks.

The decision about whether to accept intubation and ventilator support is highly personal. People who have treatable or even curable serious or life threatening illness may elect to be intubated while undergoing treatment in the hopes that, should they suffer respiratory failure from a complication like pneumonia, they will regain the ability to breathe on their own and resume treatment for their underlying illness. Others, with terminal illness where progression is inevitable may elect to decline intubation and ventilatory support and live out their lives in comfort and die a natural death at home in the company of family and friends while in hospice care.

Many patients receiving care at home from The Connecticut Hospice use CPAP and BiPAP, and some have used invasive ventilation with a tracheostomy at home. All three are options at our Branford inpatient unit.

Should you or someone you know be facing a decision about intubation and ventilatory support, the Connecticut Hospice Stand by Me Palliative Care program can provide additional counseling on treatment options in serious illness. We are here to help.

When caring for a hospice patient, making sure they receive their medications safely and comfortably is essential. Sometimes, swallowing pills can be difficult for these patients due to various conditions, including trouble swallowing, weakness, or other complications. One way to help is by crushing medications, but not all pills are safe to crush. Knowing which medications can be safely crushed and which cannot is crucial to avoid any potential harm.

This guide will cover why some medications can be crushed, which types are generally safe, which are not, and how to crush medications safely.

Many hospice patients have conditions that make swallowing pills challenging, such as:

Crushing medications can help ensure the patient gets their necessary medicine without added stress or discomfort. However, not all medications can be crushed safely, so it’s important to know which ones are suitable for crushing.

While not an exhaustive list, here are some general guidelines on the types of medications that are typically safe to crush:

Certain medications should never be crushed because it can change how they work, cause side effects, or even become dangerous. Here’s a list of common types that should not be crushed:

Here are a few common medications often used in hospice care that should not be crushed:

When crushing medications is appropriate, it’s essential to do it safely to ensure the medication is administered correctly and comfortably. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

If a medication cannot be crushed, there are alternative options:

Caring for a hospice patient involves many special considerations, including how they take their medications. Crushing pills can be a helpful solution, but it must be done with care and the guidance of a healthcare provider. Always double-check which medications can be safely crushed and explore other options if needed. Remember, the goal is to ensure that the patient remains comfortable and receives the best possible care.

If you have any questions about medication safety for your loved one, don’t hesitate to reach out to your hospice team. They are there to support you and provide guidance every step of the way.

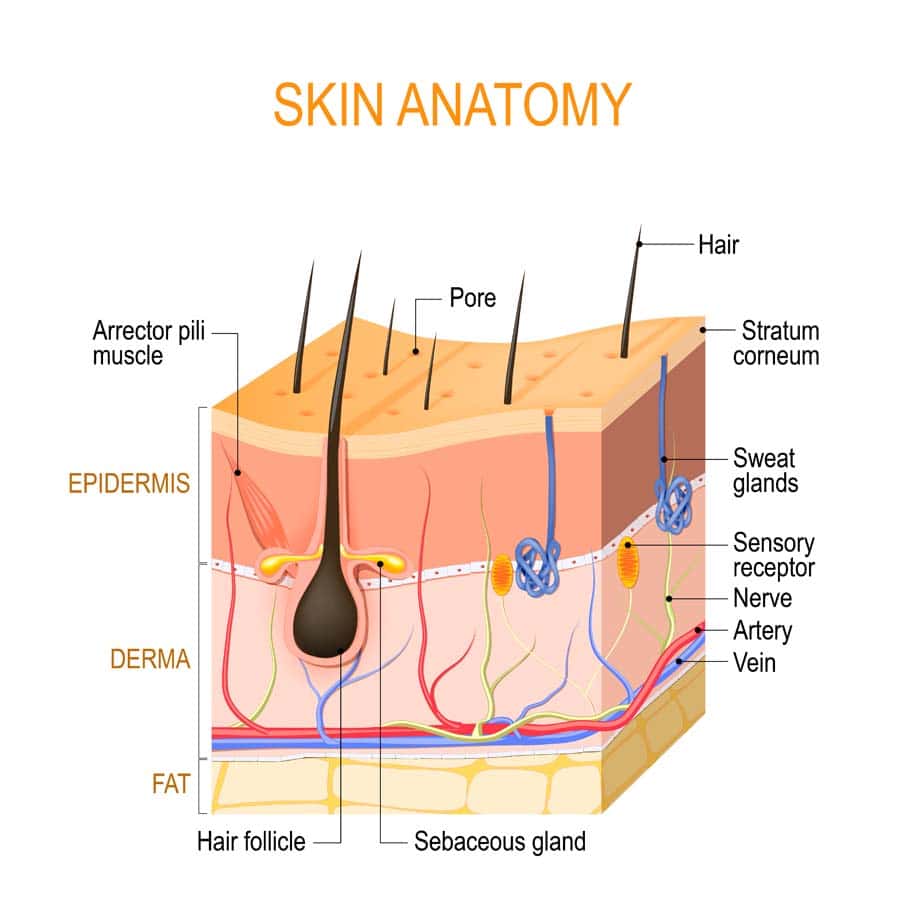

As we approach the end of life, our bodies undergo various transformations, both internally and externally. One of the most noticeable changes can be observed in our skin. Understanding these skin changes is crucial for caregivers, medical professionals, and loved ones to provide appropriate care and support. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the common skin changes that occur towards the end of life, their causes, implications, and strategies for managing them effectively. Any and all of these changes are considered a normal part of the natural dying process.

Circulatory Changes: Reduced blood flow to the skin contributes to pallor, mottling, and increased susceptibility to pressure ulcers. As the body's systems begin to shut down, blood is redirected to essential organs, leading to decreased perfusion of the skin and other peripheral tissues.

Dehydration: Diminished fluid intake or inability to process fluids properly can lead to dry, cracked skin. Dehydration is common in the end-of-life stage due to decreased oral intake, increased fluid losses, and metabolic changes.

Nutrition: Poor nutrition, common towards the end of life, can impair skin health and delay wound healing. Malnutrition, along with underlying medical conditions, can weaken the skin's structure and compromise its ability to withstand pressure and trauma.

Medications: Certain medications may affect skin integrity, moisture levels, and clotting mechanisms. For example, anticoagulants can increase the risk of bruising and bleeding, while diuretics may contribute to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

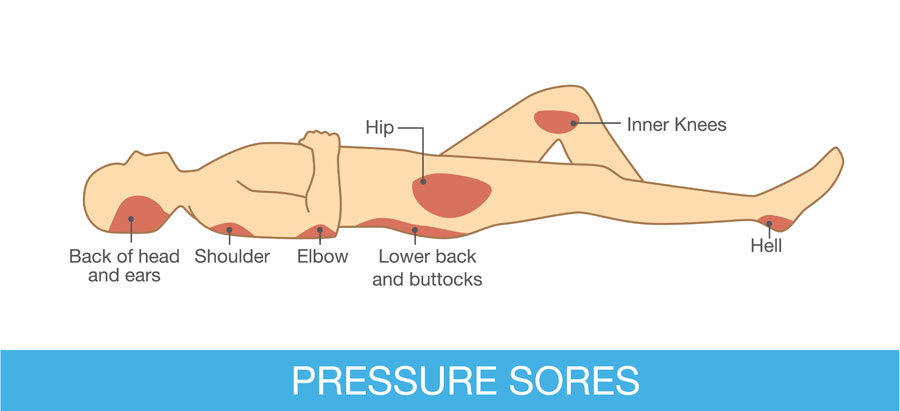

Immobility: Limited mobility increases the risk of pressure ulcers and skin tears, as well as exacerbating circulation issues. Individuals who are bedridden or confined to a wheelchair are particularly susceptible to skin breakdown due to prolonged pressure and lack of movement.

Psychological and Emotional Impact of Skin Changes in Dying Patients

Skin changes can be distressing for both the individual nearing the end of life and their loved ones. Visible alterations in skin appearance may serve as a stark reminder of the person's declining health and mortality. Discomfort and pain associated with skin issues can also exacerbate emotional distress and affect overall well-being. It is important to discuss these changes with your medical provider and for the medical team to reassure and educate loved ones that these changes are a natural part of the dying process. Open and honest communication with the individual and their caregivers is essential to address concerns and provide reassurance. Emotional support, including validation of feelings and offering comfort, can help alleviate distress related to skin changes. Collaboration with healthcare professionals, including nurses, wound care specialists, and palliative care teams, is vital for comprehensive holistic care when it comes to managing these skin changes at end of life.

Providing dignified and comfortable care for individuals experiencing skin changes at the end of life is paramount. Respect for the individual's autonomy, privacy, and preferences should guide all aspects of care, including skin care routines and interventions. Encourage the individual or family members to participate in decisions regarding their care to promote a sense of control and agency.

Maintaining privacy and modesty is essential when addressing skin changes, as individuals may feel vulnerable or self-conscious about their appearance. Respectful communication and sensitivity to cultural and personal beliefs can help preserve the individual's dignity and promote a positive care experience. Additionally, incorporating rituals or practices that hold significance for the individual, such as religious ceremonies or personal grooming habits, can enhance their sense of well-being and spiritual comfort.

By understanding the causes and implications of these changes and implementing appropriate strategies, caregivers and loved ones can help maintain the individual's comfort and dignity during this challenging time. Through open communication and compassionate care, we can support those nearing the end of life in their journey with grace and dignity.

Understanding and addressing skin changes at end of life is essential for providing holistic care to individuals nearing the end of their journey. These changes, ranging from pallor and mottling to pressure ulcers and skin tears, are natural manifestations of the body's decline and require thoughtful management to maintain comfort and dignity. By recognizing the contributing factors, implementing appropriate interventions, and fostering open communication and support, caregivers, medical professionals, and loved ones can help alleviate distress and enhance quality of life for those in their care.

As we navigate the complexities of end-of-life care, it is crucial to uphold the principles of dignity, compassion, and respect for the individual's autonomy and preferences. Each person's journey is unique, and tailoring care approaches to meet their specific needs and wishes is paramount. Through this understanding, we can ensure that individuals facing skin changes at the end of life receive compassionate and comprehensive care that honors their humanity and affirms their inherent worth. Together, we can embrace the journey with empathy and grace, providing solace and support to those embarking on life's final chapter.

Connecticut Hospice recently held a ribbon-cutting ceremony to celebrate the opening of its Palliative Care Clinic. This celebration occurred shortly after the official launch of its Palliative Care Program, Stand by Me. In addition to meeting with our clinicians at their newly launched waterfront clinic, services can also be provided at skilled nursing homes and long-term care facilities.

The Stand by Me palliative care service is a physician and APRN consultative program for the treatment of discomfort, symptoms, and stress caused by a serious illness. Palliative care works with primary medical practitioners to attain treatment goals, prevent or ease suffering, and improve quality of life. It gives patients a chance to live better, have better physical functioning, and decrease depression and anxiety.

The goal of Palliative Care is to improve the quality of life for patients being treated for serious illness. It is appropriate for all stages of treatment, starting at diagnosis. The focus is on relieving complex physical, psychological, social, and/or spiritual problems related to life-limiting or irreversible illness. It includes counseling on disease management to empower patients to better understand their illness and its treatment so they can choose the care best suited to their unique needs.

Palliative care is available to you at anytime during the course of your illness. You can meet with a palliative specialist as little or more often as needed. Palliative care does not mean you are dying, it is about living better, healthier, and being as comfortable as possible. This all leads to a better quality of life and better engagement with loved ones. Very often, people under palliative care continue treatment of their disease and stabilize and graduate from the service. Palliative care is about living long and well!

Learn more about our Outpatient Palliative Care Services

You should not have to endure unnecessary suffering from symptoms of disease or treatment. We respond promptly to calls for assistance, offering 24/7 support. We understand the urgency of your needs and can swiftly schedule in-person visits with our full-time Advanced Practice Registered Nurse, ensuring expert symptom management and counseling on disease management options within days, not months.

Call today to schedule an appointment: 203-315-7540

Click the links below to learn more about Palliative care vs. Hospice care.

Compassionate Care: Hospice vs. Palliative Care Insights

Palliative Care vs. Hospice Care—What You Need to Know

Mother of a Cancer Patient Authors a Guide to Palliative Care

Facing the end of life is a profound and emotional experience for both individuals and their loved ones. In these challenging moments, it's essential to comprehend the various aspects of the dying process, including some common breathing patterns that often emerge at end of life. This blog post aims to shed light on end-of-life breathing patterns, exploring their manifestations, mechanisms, and the compassionate approaches available for treatment.

As individuals approach the end of life, changes in breathing patterns are common and can be indicative of the body's transition towards death. These alterations are part of the natural dying process and often occur as a result of the body's decreasing energy levels and organ systems shutting down. It's crucial to recognize that each person's journey is unique, and breathing patterns may vary. For some, these common patterns may be present, and for others none of these will occur.

Understanding end-of-life breathing patterns is a crucial aspect of providing compassionate care to those nearing the end of their journey. It's essential to approach these situations with empathy, patience, and a commitment to maintaining the dignity and comfort of the individual. By combining medical knowledge with emotional and spiritual support, we can ensure that the final moments of life are as peaceful and meaningful as possible for both the person and their loved ones as they take their final breathes.

Dementia has several different forms, including Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy Body dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s Disease-related dementia, and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. All forms of the disease with the exception of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, are terminal and last an average of seven to ten years, robbing people of their cognitive abilities, personality, and ability to care for themselves. Ultimately, people with dementia become bedbound and unable to talk, lose their appetites, stop eating, and become unrecognizable, emaciated versions of their once robust selves – devoid of the unique qualities that make each of us special.

Complications such as difficulty eating and aspiration – inhaling food and fluid – with consequent pneumonia, and urinary tract infections and bedsores are very common. Other, later consequences of dementia, not necessarily seen in all people with this disease, are restlessness, agitation, combativeness, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Some dementias, such as Lewy Body dementia, are accompanied by hallucinations and delusions, including paranoia.

The management of dementia is time consuming, requiring dedication and patience as afflicted individuals become increasingly – and eventually completely -- dependent on caregivers for day-to-day activities such as eating, bathing, and dressing. Ongoing, high quality bedside care is essential to avoid – to the extent possible -- complications such as bedsores and aspiration. Failing to turn and reposition a bedbound elder for as little as five to ten hours can initiate a bedsore, which can rapidly progress to a deep, infected, ugly wound. Likewise, people with dementia should never be force fed – even so much as putting food in their mouths when they show no interest in eating – as this will almost guarantee their inhaling these oral contents into their lungs and getting pneumonia.

Reversal of cognitive injuries associated with dementia such as impaired memory and loss of executive function – like the ability to balance a checkbook or make a phone call -- is currently not possible; medications including oral cholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine (Exelon) and donepezil (Aricept) and the new FDA-approved intravenous antibody therapies aducanumab (Aduhelm) and lecanemab (Leqembi) – administered every two to four weeks and costing $25,000 -- $30,000 per year – are used in early to moderate dementia to slow the progression of the disease and show varying efficacy – working better in some than others. The effects of these medications on everyday activities such as the ability to dress independently -- in contrast to delaying loss of memory and cognition -- are also variable, not possible to predict in any given individual, and may be minimal. Another concern is side effects; cholinesterase inhibitors commonly cause nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, decreased appetite, stomach upset, muscle cramps, fatigue, insomnia, dizziness, headache, and lack of energy, while the newer therapies may cause swelling and bleeding in the brain.

Several approaches may help to manage behavioral problems such as combativeness and agitation and should start with a search for underlying causes such as an infection or pain. Agitation caused by a medical condition is called delirium, which when treated may lead to resolution of the behavior and a far calmer loved one. Many elders with dementia have chronic painful conditions such as osteoarthritis or spinal stenosis and express their distress with restlessness and behaviors like repeatedly climbing out of bed instead of using words to describe their distress; this makes a trial of mild analgesics such as Tylenol a reasonable first step. Some may need more potent drugs such as opioids, as is seen commonly in hospice patients with dementia. Bedsores, for example, can be very painful. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) may also cause delirium, with the behavior resolving after a course of antibiotics. In the absence of obvious symptoms such as painful urination, flank pain, or fever, which may merit starting antibiotics immediately, however, investigation of UTI requires a urine culture to establish the diagnosis and avoid potential serious side effects of antibiotics such as severe allergy causing difficulty breathing or clostridium difficile diarrhea – “c diff” – which can be life threatening and easily spread to other, healthy people.

Other means of calming an agitated elder are environmental and behavioral, such as assuring a calm, quiet, familiar setting, soothing music, offering food when desired, turning out lights and turning down noise at night to allow sleep, and the presence of known loved ones. A chaotic, unfamiliar environment, with strangers randomly coming in and out of the room, absence of friends and family, constant light and noise, and painful procedures that interfere with sleep such as 5AM blood tests – done at this hour in hospitals to make results available for doctors’ morning rounds – may precipitate agitation, or make preexisting agitation worse. Hospitalization, often characterized by these negative environmental factors, can not only precipitate agitation, but accelerate the cognitive impairments and loss of ability for self-care that characterize dementia. Hospice staff hear again and again about elders with mild dementia who were still able to care for themselves before being hospitalized who were rendered bedbound and fully incapable of self-care after a one-week hospital stay. Sometimes, hospice staff are able to calm elderly people simply by seating them in a recliner at the nurse’s station and talking to them as they go about their business.

Underlying psychiatric illness such as depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychosis such as schizophrenia may also trigger behavioral disturbances in demented elders, making treating these conditions – especially in people with preexisting diagnoses of psychiatric illness – another approach.

Finding an underlying cause of agitation is, unfortunately, the exception and not the rule in dementia, making the use of medications to try to treat delirium of unknown cause a reasonable next step. This, too, can prove difficult and is hit or miss. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate which drug works best for which type of behavioral problem in which type of dementia, with mixed and limited findings. Drugs used include cholinesterase inhibitors, antidepressants including selective serotonin inhibitors such as escitalopram (Lexapro), sedatives such as trazodone (Desyrel) and lorazepam (Ativan), intended to improve sleep, anti-anxiety agents such as diazepam (Valium) and lorazepam, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine (Tegretol), and antipsychotics such as haloperidol (Haldol), risperidone (Risperdal), and quetiapine (Seroquel). It is always the goal of hospice staff to try to calm elders without sedating them so they can engage meaningfully with family and friends.

We treat pain and urinary infections where appropriate, establish a calm and soothing environment, assign staff and volunteers to sit at the bedside to talk and read to patients, have members of our arts department play live music for them, seat them collegially at the nurse’s station, try to assure their sleep with moderate doses of sedatives at night in a dark, quiet room, and allow their loved ones to visit 24-7. If these interventions don’t work, we use antipsychotics and other medications that are less sedating and do not escalate to higher doses of sedating agents until all other interventions have been tried and exhausted. At times, rendering someone sleepy or unconscious may be the only way to relieve agitated delirium, a symptom that may be as distressing for our patients and their loved ones as severe pain or shortness of breath.

In all cases, our goal is to maintain the dignity and humanity of all of our patients to the extent that is humanly – and medically – possible.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.