Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Facing the end of life is a profound and emotional experience for both individuals and their loved ones. In these challenging moments, it's essential to comprehend the various aspects of the dying process, including some common breathing patterns that often emerge at end of life. This blog post aims to shed light on end-of-life breathing patterns, exploring their manifestations, mechanisms, and the compassionate approaches available for treatment.

As individuals approach the end of life, changes in breathing patterns are common and can be indicative of the body's transition towards death. These alterations are part of the natural dying process and often occur as a result of the body's decreasing energy levels and organ systems shutting down. It's crucial to recognize that each person's journey is unique, and breathing patterns may vary. For some, these common patterns may be present, and for others none of these will occur.

Understanding end-of-life breathing patterns is a crucial aspect of providing compassionate care to those nearing the end of their journey. It's essential to approach these situations with empathy, patience, and a commitment to maintaining the dignity and comfort of the individual. By combining medical knowledge with emotional and spiritual support, we can ensure that the final moments of life are as peaceful and meaningful as possible for both the person and their loved ones as they take their final breathes.

Dementia has several different forms, including Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy Body dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s Disease-related dementia, and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. All forms of the disease with the exception of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, are terminal and last an average of seven to ten years, robbing people of their cognitive abilities, personality, and ability to care for themselves. Ultimately, people with dementia become bedbound and unable to talk, lose their appetites, stop eating, and become unrecognizable, emaciated versions of their once robust selves – devoid of the unique qualities that make each of us special.

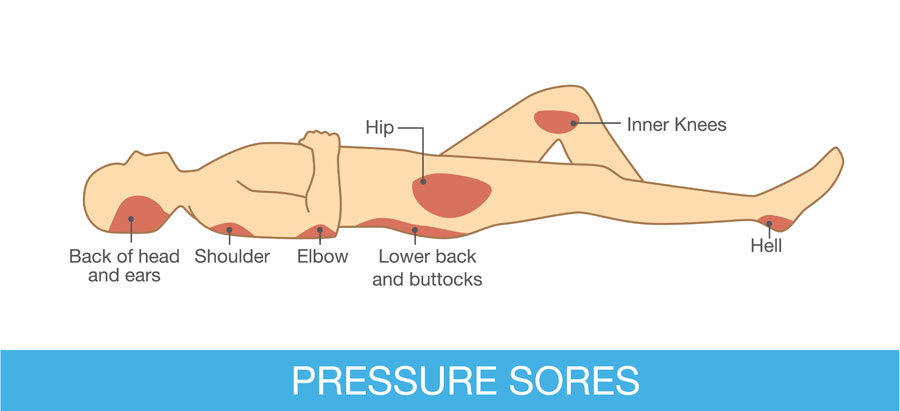

Complications such as difficulty eating and aspiration – inhaling food and fluid – with consequent pneumonia, and urinary tract infections and bedsores are very common. Other, later consequences of dementia, not necessarily seen in all people with this disease, are restlessness, agitation, combativeness, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Some dementias, such as Lewy Body dementia, are accompanied by hallucinations and delusions, including paranoia.

The management of dementia is time consuming, requiring dedication and patience as afflicted individuals become increasingly – and eventually completely -- dependent on caregivers for day-to-day activities such as eating, bathing, and dressing. Ongoing, high quality bedside care is essential to avoid – to the extent possible -- complications such as bedsores and aspiration. Failing to turn and reposition a bedbound elder for as little as five to ten hours can initiate a bedsore, which can rapidly progress to a deep, infected, ugly wound. Likewise, people with dementia should never be force fed – even so much as putting food in their mouths when they show no interest in eating – as this will almost guarantee their inhaling these oral contents into their lungs and getting pneumonia.

Reversal of cognitive injuries associated with dementia such as impaired memory and loss of executive function – like the ability to balance a checkbook or make a phone call -- is currently not possible; medications including oral cholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine (Exelon) and donepezil (Aricept) and the new FDA-approved intravenous antibody therapies aducanumab (Aduhelm) and lecanemab (Leqembi) – administered every two to four weeks and costing $25,000 -- $30,000 per year – are used in early to moderate dementia to slow the progression of the disease and show varying efficacy – working better in some than others. The effects of these medications on everyday activities such as the ability to dress independently -- in contrast to delaying loss of memory and cognition -- are also variable, not possible to predict in any given individual, and may be minimal. Another concern is side effects; cholinesterase inhibitors commonly cause nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, decreased appetite, stomach upset, muscle cramps, fatigue, insomnia, dizziness, headache, and lack of energy, while the newer therapies may cause swelling and bleeding in the brain.

Several approaches may help to manage behavioral problems such as combativeness and agitation and should start with a search for underlying causes such as an infection or pain. Agitation caused by a medical condition is called delirium, which when treated may lead to resolution of the behavior and a far calmer loved one. Many elders with dementia have chronic painful conditions such as osteoarthritis or spinal stenosis and express their distress with restlessness and behaviors like repeatedly climbing out of bed instead of using words to describe their distress; this makes a trial of mild analgesics such as Tylenol a reasonable first step. Some may need more potent drugs such as opioids, as is seen commonly in hospice patients with dementia. Bedsores, for example, can be very painful. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) may also cause delirium, with the behavior resolving after a course of antibiotics. In the absence of obvious symptoms such as painful urination, flank pain, or fever, which may merit starting antibiotics immediately, however, investigation of UTI requires a urine culture to establish the diagnosis and avoid potential serious side effects of antibiotics such as severe allergy causing difficulty breathing or clostridium difficile diarrhea – “c diff” – which can be life threatening and easily spread to other, healthy people.

Other means of calming an agitated elder are environmental and behavioral, such as assuring a calm, quiet, familiar setting, soothing music, offering food when desired, turning out lights and turning down noise at night to allow sleep, and the presence of known loved ones. A chaotic, unfamiliar environment, with strangers randomly coming in and out of the room, absence of friends and family, constant light and noise, and painful procedures that interfere with sleep such as 5AM blood tests – done at this hour in hospitals to make results available for doctors’ morning rounds – may precipitate agitation, or make preexisting agitation worse. Hospitalization, often characterized by these negative environmental factors, can not only precipitate agitation, but accelerate the cognitive impairments and loss of ability for self-care that characterize dementia. Hospice staff hear again and again about elders with mild dementia who were still able to care for themselves before being hospitalized who were rendered bedbound and fully incapable of self-care after a one-week hospital stay. Sometimes, hospice staff are able to calm elderly people simply by seating them in a recliner at the nurse’s station and talking to them as they go about their business.

Underlying psychiatric illness such as depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychosis such as schizophrenia may also trigger behavioral disturbances in demented elders, making treating these conditions – especially in people with preexisting diagnoses of psychiatric illness – another approach.

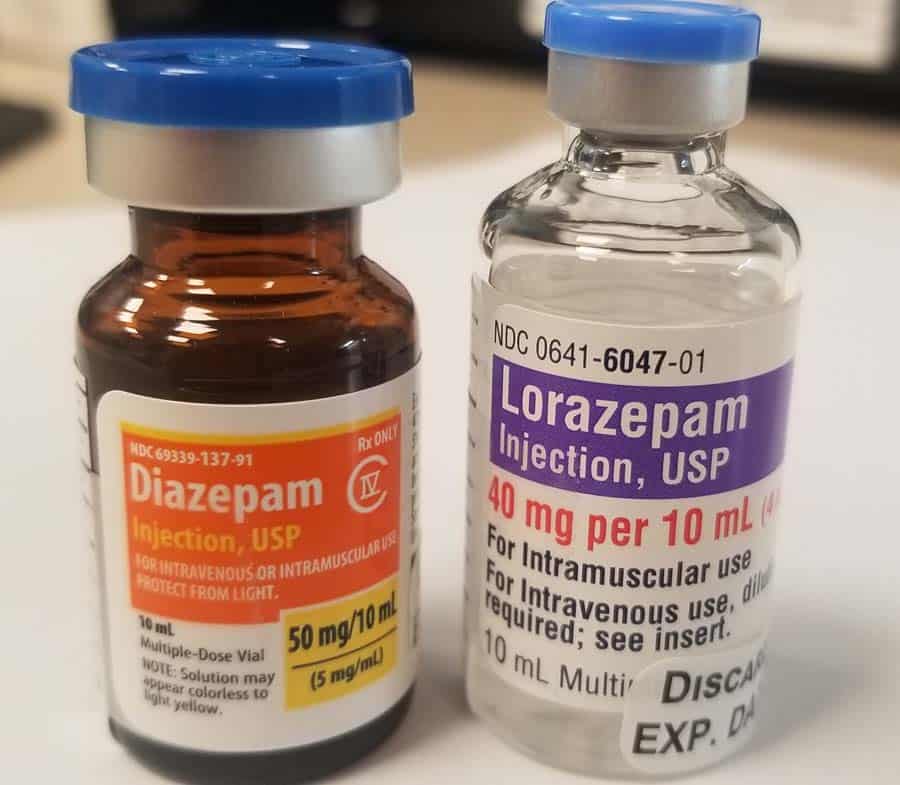

Finding an underlying cause of agitation is, unfortunately, the exception and not the rule in dementia, making the use of medications to try to treat delirium of unknown cause a reasonable next step. This, too, can prove difficult and is hit or miss. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate which drug works best for which type of behavioral problem in which type of dementia, with mixed and limited findings. Drugs used include cholinesterase inhibitors, antidepressants including selective serotonin inhibitors such as escitalopram (Lexapro), sedatives such as trazodone (Desyrel) and lorazepam (Ativan), intended to improve sleep, anti-anxiety agents such as diazepam (Valium) and lorazepam, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine (Tegretol), and antipsychotics such as haloperidol (Haldol), risperidone (Risperdal), and quetiapine (Seroquel). It is always the goal of hospice staff to try to calm elders without sedating them so they can engage meaningfully with family and friends.

We treat pain and urinary infections where appropriate, establish a calm and soothing environment, assign staff and volunteers to sit at the bedside to talk and read to patients, have members of our arts department play live music for them, seat them collegially at the nurse’s station, try to assure their sleep with moderate doses of sedatives at night in a dark, quiet room, and allow their loved ones to visit 24-7. If these interventions don’t work, we use antipsychotics and other medications that are less sedating and do not escalate to higher doses of sedating agents until all other interventions have been tried and exhausted. At times, rendering someone sleepy or unconscious may be the only way to relieve agitated delirium, a symptom that may be as distressing for our patients and their loved ones as severe pain or shortness of breath.

In all cases, our goal is to maintain the dignity and humanity of all of our patients to the extent that is humanly – and medically – possible.

Hospice care is a specialized form of healthcare that focuses on enhancing the quality of life for individuals with terminal illnesses. The goal is to provide comfort, support, and dignity during the end-of-life journey. However, the use of medications, particularly benzodiazepines, have been both a blessing and a controversy in end-of-life care. In this blog post, we will explore the role of benzodiazepines in hospice care, the benefits they offer, potential drawbacks, and the ethical considerations surrounding their use.

Benzodiazepines are a class of sedative drugs that act on the central nervous system. They are commonly prescribed to alleviate symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. These medications produce a calming and sedative effect. Examples of benzodiazepines include diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and alprazolam (Xanax). While these medications can be highly effective in managing certain conditions, their use in hospice care requires careful consideration.

The use of benzodiazepines in hospice care requires thoughtful reflection. Key considerations include:

Palliative sedation is a carefully regulated and monitored medical intervention that is employed when other forms of symptom management have proven ineffective. It is typically reserved for patients experiencing severe distress, refractory symptoms, or existential suffering that cannot be alleviated through conventional means. Palliative sedation aims to balance the relief of symptoms with the preservation of patient comfort and dignity. Benzodiazepines, a class of sedative drugs, are frequently employed in palliative sedation due to their effectiveness in promoting a peaceful and comfortable experience for patients nearing end of life.

The use of benzodiazepines for palliative sedation in hospice care is a complex but widely ethically accepted practice. These medications offer effective symptom control and rapid onset of sedation, and their use requires careful consideration of individual patient needs, open communication, and adherence to ethical practice – long a core principal of patient care at Connecticut Hospice. The goal of hospice physicians who employ palliative sedation is always the enhancement of patient comfort and dignity during the final stages of life. By embracing a patient/family-centered, multidisciplinary approach, healthcare professionals can provide compassionate care that honors the values and preferences of those under their charge, ensuring a peaceful and dignified journey toward the end of life.

The use of benzodiazepines in hospice care requires careful consideration of medical, ethical, and patient-centered factors by experienced physicians and nurses. These medications offer valuable benefits in managing symptoms associated with terminal illnesses; patients and families may be assured that the healthcare providers at Connecticut Hospice expertly navigate all potential concerns associated with their use. Open communication, informed consent, and regular reassessment are key components of a comprehensive approach to benzodiazepine use in hospice care, ensuring that the patient's final journey is characterized by comfort, dignity, and respect for their autonomy.

Announced in 1978 by then President Jimmy Carter, the month was established to recognize the efforts of those who provide end-of-life care, and to help raise awareness of the growing hospice movement. By the time of this designation, Connecticut Hospice, America’s first, had already been providing high-quality care to hospice patients for 5 years.

We have come a long way since 1978. President Carter is now a hospice patient. Hospice is well-established in the United States and around the world; 1.7 million American Medicare beneficiaries will avail themselves of hospice care in 2023.

Ironically, despite this progress, most people do not know the difference between hospice and palliative care. So, in honor of National Hospice and Palliative Care Month, this blog will be a primer on two very distinct medical specialties.

Hospice is a benefit -- an entitlement, like Social Security, provided by Uncle Sam -- available to people whom a physician estimates to have six months or less to live if their illness progresses through its natural course and who have declined further treatment in favor of focusing on the quality of the life they have remaining. Most hospice programs are financed by Medicare – at no cost to patients -- though many other insurers, including Medicaid, offer hospice benefits. All hospices must provide a specific set of services to the patients they enroll, including skilled nursing and medical services, social work, chaplaincy, volunteer, and other professional services.

While both hospice and palliative care are part of the same medical specialty, complete with post-residency fellowships and, since 2006, board certification, palliative care is distinct from hospice. Appropriate for all people with serious illness, including those still seeking treatment of their disease -- an important distinction from hospice -- palliative care helps patients and their loved ones understand the condition, treatment options, and likely disease trajectory so they may make informed choices that align with their goals and wishes. It also provides expert management of symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath, and nausea, helps people obtain non-medical assistance like help in the home, and may even provide medical management of the disease and its complications.

I had the privilege of providing palliative care to two patients who exemplify the specialty at its best. One, a woman in her fifties, was diagnosed with a malignancy and referred to a home palliative care program I worked with. She was suffering from pain and anxiety, and the nurses, social workers and I collaborated to provide her relief from these symptoms with counseling, support, and medications. Literate, educated, and a self-starter, she then set about finding a leading physician to offer treatment for her disease.

When she returned from her first appointment she was confused.

“What did he say?” I asked during a home visit.

“I didn't understand a word of it,” she told me, exasperated. “I’m not even sure he was speaking English.”

This was not at all uncommon. Though well-intended, doctors often struggle to make medical information understandable for their patients, who typically do not have medical training. Palliative care doctors specialize in exactly this kind of conversation.

“Would you like me to call him and find out what he can do for you and let you know?” I asked.

She did. I returned to her home a few days later and got straight to the point, cutting through the medical esoterica that had characterized my discussion with the surgeon -- and, apparently, what he had told her. “The surgeon said you have a better than 80% chance of being cured with an operation,” I told her.

“Would you do it?” she asked.

“Those are pretty good odds,” I said. “I'd go for it.”

That was more than five years ago. I still get Christmas cards from her. Cured, she returned to her life and no longer needs palliative care.

The second was a man in his late 60s. Retired, he had recently lost his beloved wife, and suffered from advanced cancer that left him fatigued and mostly unable to get up from the couch in his living room. He'd been suffering from cancer for 10 years; his oncologist had managed again and again to find a treatment to prolong his life.

He had thought about his condition and was direct about his wishes. “So long as my doctor can keep my cancer in check,” he said, “I'm going to keep getting treated. But when it stops working, I'm going to enroll in hospice so I can die in comfort.”

I was impressed. “What do you like to do?” I asked. “For fun?”

“Fish,” he said without hesitation. “Trout. Catch and release. I even have a blog. But I'm too tired for that now,” he said with a resigned frown. “I can barely get off this couch.”

I had some tricks up my sleeve. I started him on a brief course of high dose corticosteroids and amphetamine. He virtually leapt from his couch, donned his floppy fishing hat and khaki vest, festooned with flies he had tied himself, climbed into his pickup truck, picked up his son, and spent a day catching trout and throwing them back into one of his favorite fishing spots.

I stopped the medications and he flopped back on his couch. Six months later he was admitted to our inpatient hospice facility. Treatment was no longer holding back his cancer and he had worsening shortness of breath.

I stopped in at his bedside on the morning of his admission. “How can we help?” I asked.

He answered with his characteristic lack of hesitation. “I want to stop feeling short of breath, I want to see my son get married, and I want to die in peace,” he replied.

His son stood on the opposite side of the bed. “When are you getting married?” I asked him.

“In three months,” he replied.

Later, we spoke in the hall. “You're getting married tomorrow at your dad's bedside,” I said.

“I think you misunderstood doc,” he said. “I'm getting married in three months.”

“I understood,” I said, “but I'm asking you to get married tomorrow at your dad's bedside.”

He and his fiancé married the following day in a ceremony attended by most of the hospice staff. He wore a tuxedo and she a wedding gown. There was music, dancing and champagne – right in his father’s room. His father could not stop smiling. He died peacefully the following day.

Connecticut Hospice is proud to launch a palliative care program, which will be fully operational in December. Our APRN, social workers, and chaplaincy will be offering palliative care to patients who are self-referred, or referred by friends, family, or by their doctors. We will see patients in a brand-new clinic in our inpatient facility in Branford, by telehealth, and in people's homes or in skilled nursing, assisted living, or independent living facilities.

For more information about our new palliative care program, call 203-315-7540.

Opioids are a critical means of relieving pain and shortness of breath in people with serious illnesses. While non-opioid analgesics such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) may partially or fully relieve mild to moderate pain, these agents have no effect on shortness of breath, and opioids are usually required for more severe pain.

Before describing different opioids and how and when to use them, let’s review some broadly held concerns about this class of medication.

First, and perhaps most importantly, is the belief that opioids cause respiratory depression and hasten dying. There is no question that opioids can slow respiration, especially if used incorrectly or given in high doses. However, the reality is that respiratory depression with opioids in the setting of life-limiting illness is rare. A well-conducted study of opioids in cancer patients with shortness of breath conducted 30 years ago showed that these medications were effective in relieving symptoms and resulted in no significant respiratory depression (Bruera E, MacEachern T, Ripamonti C, Hanson J. Subcutaneous morphine for dyspnea in cancer patients. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(9):906–907). Another study, conducted in 2002, showed that opioids are also safe and effective for the treatment of shortness of breath or pain in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure (Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, Gibbs JS, Broadley KE. A systematic review of the use of opioids in the management of dyspnoea. Thorax. 2002;57(11):939–944).

Unfortunately, the belief that opioids hasten dying persists among both medical and nursing professionals and the public at large. The physicians and nurse practitioners at The Connecticut Hospice, Inc. are highly experienced in the safe use of opioids, making this concern unnecessary for the care of you or a loved one. While the use of very high doses of opioids at the very end of life in patients who are not conscious may result in some respiratory slowing, this is never the reason they are used, which is solely to effect relief of pain and shortness of breath in patients who are suffering.

Another widely held perception about opioids is that they necessarily cause addiction, or opioid use disorder (OUD). Unfortunately, as with beliefs about respiratory depression, the consensus around the medical use of opioids and OUD is nuanced and merits closer examination.

CDC Guidelines: Shaping the Landscape of Opioid Use

First, there is no question that the inappropriate use of opioids in the medical setting, especially in the 2000s, contributed to the spread of OUD and the opioid epidemic, which in 2021 took the lives of 106,000 of our friends, neighbors, and family members. Aggressive marketing of opioids for medical use and the overprescribing of opioids for both acute pain (“acute” meaning of recent onset, such as for a broken bone or dental problem) and chronic pain clearly resulted in OUD and death in some patients. Partially in response to this, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) issued guidelines in 2016 on the use of opioids for pain. While the report made clear that the evidence on harm related to the medical use of opioids was less than optimal, they recommended nonopioid pharmacologic therapy as preferred for chronic pain, with numerous caveats and warnings for those patients with chronic pain who were prescribed opioids. For people with acute pain, no more than a 3-to-7-day supply of opioids was recommended. A wave of legislation and regulatory actions on the medical use of opioids followed, resulting in an almost 50% decline in opioid prescribing from 2016 to 2019. The CDC updated these guidelines in 2022, still recommending non-opioid therapy for chronic pain, though also stating, “No validated, reliable way exists to predict which patients will experience serious harm from opioid therapy and which patients will benefit from opioid therapy.” The report softened its position regarding acute pain, stating, “When opioids are needed for acute pain, clinicians should prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids.”

Unfortunately, these reports – and the legislation that followed -- created barriers to effective pain relief for many people with chronic pain who previously had good symptom relief with little or no harm from opioids prescribed by experienced clinicians. In the hospice context, the risk of OUD-related harm is exceedingly low when seriously ill patients with moderate to severe pain are managed by appropriately trained medical staff. This is not because expected death renders the development of OUD irrelevant, but because -- at least in my experience with thousands of patients -- OUD does not occur when pain and shortness of breath are appropriately managed with opioids. This includes many patients who were treated for and cured of serious illness or painful orthopedic conditions who successfully stopped taking appropriately prescribed opioids without developing OUD.

In short, OUD is not a concern for hospice patients – and it should be noted that both CDC guidelines specifically exclude patients at the end of life from their recommendations.

Opioids fall into three distinct chemical categories, those related to morphine, such as codeine, oxymorphone (Opana), oxycodone (including OxyContin), buprenorphine (various brand names, including Suboxone), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab), those related to fentanyl, and those related to methadone.

Practically, the opioids are divided by duration of action and potency. Most, including those commonly used in hospice, such as morphine and hydromorphone, provide relief of pain and shortness of breath for about 4 hours. Some of these come in longer-acting oral formulations, such as MSContin and OxyContin, which last 6 to 8 hours and only exist in oral form (remember that long-acting pills will lose their 6 – 8 hour duration of action if they are crushed). Morphine and hydromorphone also come in oral concentrates, which need only be taken under the tongue to work (making them effective for people who have difficulty swallowing), and injected forms. Typically, oral opioids (swallowed or under the tongue) take about 30 to 45 minutes to take effect, IV forms work in 5 – 15 minutes, and those given by intramuscular injection or under the skin (“sub-q”) take about 15 – 20 minutes to work. Oxycodone only has an oral form. The potency of opioids is usually contrasted with morphine and referred to as oral morphine milligram equivalent, or MME. Hydromorphone is roughly 4 – 7 times as potent as morphine, and oxycodone about 1.5 times as potent. Injected opioids are more potent than oral opioids – doses of oral opioids are reduced by half to a third when patients are no longer able to take them by mouth and they are given by injection.

At Connecticut Hospice, we generally start with lower opioid doses given on an as-needed basis for patients who have not previously used opioids (“opioid-naïve”), and we escalate the dose and give it on a scheduled rather than as needed basis as the opioid requirement becomes clear in the first day or two of their use. We always try to schedule these medications to prevent pain or shortness of breath before it starts, rather than relieving it after it has started. Opioid-experienced patients will be escalated as needed from prior dose regimens.

What’s a normal opioid dose? – very variable. Often we start at a dose of morphine 2 mg injected every 4 hours (“Q4H”) in our inpatient unit with the same dose available every 20 minutes as needed (“PRN”) should the scheduled dose be ineffective and an “in-between” dose needed for persistent pain. Hydromorphone 0.4 mg injected Q4H and Q20min PRN is also typical. We then escalate the dose as needed to fully control pain or shortness of breath. While most people need about 5 – 20 mg of injected morphine Q4H or 4 – 8 mg of injected Dilaudid Q4H for effective symptom relief, it is not unusual to get into the thousands of MMEs per day. For this reason, we often say that there is no “ceiling dose” for opioids. (Once, a patient in home care was taking 1300 mg of methadone a day for pain. She was wide awake and able to get around without sleepiness and without pain. Her only complaint was the need to take 130 ten-milligram tablets of methadone every day. By way of comparison, the dose of methadone typically used for the treatment of OUD ranges from about 50 to 150 mg daily.)

Opioid dose is adjusted based on several factors. First, does the dose relieve all the pain? If not, it needs to be increased. Second, does the pain relief last until the next dose? If not, we may need to either increase the dose or decrease the dose interval (e.g., from every 4 to every 3 hours).

How do we choose which opioid to use? Often, this depends on our pharmacy supply. Sometimes, one opioid is preferred over another, depending on a patient’s medical problem. For example, morphine is generally avoided in patients with kidney failure because it can accumulate with a resulting increased likelihood of toxicity or side effects.

Fentanyl is also commonly used in hospice. Fentanyl, which comes in a patch or “transdermal” form that is applied to the skin and replaced every three days, can be very convenient. People need a bit of body fat under the skin for it to work properly, and the medicine will not last 3 days in very underweight people with no fat under the skin.

Methadone is also a very effective opioid. Generally, it is reserved for use in patients still experiencing pain on high doses of short-acting medications such as hydromorphone and morphine. Methadone helps reverse the development of tolerance to other opioids, helping them work in patients who may have been using opioids for a prolonged period and are experiencing reduced effectiveness despite increasing dose – “tolerance.” Methadone can also help people with the painful numbness in the hands and feet – “neuropathy”-- that can affect many patients on chemo- and immune-therapy.

All opioids have side effects – though not the problems with respiratory depression and addiction often ascribed to them, as reviewed above. ALL opioids cause constipation, and patients who are not taking preventive laxatives such as senna or docusate will develop constipation that can be severe and difficult and uncomfortable to overcome. (In fact, most anti-diarrhea medications are weak opioids.) All opioids also cause sleepiness, though the effect usually wears off after a week to 10 days. In hospice, opioid-induced somnolence can be very distressing to families who want to engage with an awake and lucid loved one who is at the end of life, and finding a balance between sedation and pain control can be tricky. For some, a dose of oral methylphenidate, a mild stimulant best known as Ritalin, used for attention deficit disorder, taken in the morning and early afternoon, can help maintain wakefulness while still offering effective pain relief and allowing a night of sleep. Opioids may also cause nausea and a cloudy sensorium. While meds exist to counter these effects, such as haloperidol for nausea, rotating the opioid from, say, morphine to hydromorphone, is often all that is necessary.

Finally, there is the phenomenon of opioid-induced hyperalgesia – a rare condition in which the opioid increases pain sensitivity, resulting in sometimes severe pain from both painful and non-painful stimuli – such as simply being gently touched. This tends to be seen in patients whose pain does not get better – and seems to be getting worse – despite escalating opioid dose, sometime to very high levels. Once hyperalgesia is diagnosed and opioid dose reduced, pain often goes away.

Adjuvants are medications used to help opioids work. A benzodiazepine such as Ativan, for example, used in conjunction with an opioid in a patient with anxiety, can make the opioid more effective. NSAIDS, such as the over-the-counter analgesics ibuprofen and naproxen, have an anti-inflammatory effect and help opioids work. NSAIDS must be used with caution however, as they can cause gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney failure (typically, NSAIDs used for more than a few days are given with an antacid like omeprazole). The literature cites upwards of 16,000 deaths annually due to NSAID-induced gastrointestinal bleeding. Corticosteroid medications such as prednisone and dexamethasone (Decadron) are also powerful anti-inflammatory drugs commonly used as adjuvants for opioids, especially in people with cancer and in those with metastases (spread of cancer) to bone, which can be very painful. Like NSAIDS, corticosteroids have toxicities, including GI bleeding, and are usually used with antacids.

Dementia is a complex and debilitating condition characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and impaired daily functioning. As the disease progresses, patients often reach an advanced stage where their functional abilities decline significantly. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) serves as a valuable instrument for assessing and staging the progression of dementia, particularly in its advanced stages. This blog post aims to delve into the FAST, elaborate on the score needed for hospice eligibility, describe common characteristics of end-stage dementia, and touch upon different types of dementia and highlight how the decline can vary among these types.

The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) is a widely recognized and validated instrument used to assess the functional abilities of individuals with dementia. It was developed by Barry Reisberg, MD, and his colleagues in the late 1980s to provide a structured framework for staging the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia based on functional impairment. The FAST consists of seven stages, each representing a distinct level of cognitive and functional decline.

| FAST Score | Dementia Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | No Cognitive Decline | Normal cognitive function and memory. No observable symptoms of dementia. |

| Stage 2 | Very Mild Cognitive Decline | Slight cognitive changes attributed to aging. Forgetfulness and mild difficulty finding words. |

| Stage 3 | Mild Cognitive Decline | Noticeable cognitive impairment. Frequent memory lapses. Challenges in work or social settings. |

| Stage 4 | Moderate Cognitive Decline | More pronounced cognitive deficits. Intensified memory loss, reduced problem-solving, and attention. |

| Stage 5 | Moderately Severe Cognitive Decline | Significant cognitive and functional deficits. Memory deterioration, confusion about time/place. |

| Stage 6 | Severe Cognitive Decline | Profound cognitive impairment. Difficulty recognizing loved ones, memory loss, personality changes. |

| Stage 7 | Very Severe Cognitive Decline (Subclassification A-F) | Total functional dependence. Challenges in mobility, communication, and basic tasks. |

| 7A | Speaks 5-6 words during the day | Limited verbal communication ability. |

| 7B | Speaks only 1 word clearly | Severely restricted verbal communication. |

| 7C | No longer can walk without assistance | Mobility challenges, walking assistance required. |

| 7D | Can no longer sit up | Inability to sit up unassisted. |

| 7E | Can no longer smile | Loss of ability to smile. |

| 7F | Can no longer hold their head up | Inability to hold head up without assistance. |

The FAST score assists healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families in assessing the level of cognitive and functional decline, enabling them to provide appropriate care and support tailored to each stage. By understanding the implications of each stage, individuals can ensure the best quality of life for those living with Alzheimer’s dementia while navigating the challenges that arise throughout its progression. It's important to note that while the FAST provides a structured framework for understanding Alzheimer’s dementia progression, the exact experience can vary among individuals. Additionally, the rate at which individuals progress through the stages may differ based on factors such as the type of dementia, overall health, and individual characteristics.

Hospice care is a specialized form of medical care aimed at providing comfort, support, and quality of life for individuals with life-limiting illnesses, including advanced dementia and neurocognitive disorders. Determining hospice eligibility involves a comprehensive assessment of the patient's medical condition, functional status, and prognosis. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) score, along with Medicare's Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for dementia and neurocognitive disorders, plays a significant role in determining hospice eligibility for individuals with these conditions. Generally, a FAST score of 7A or higher is considered indicative of end-stage dementia, indicating that the individual's cognitive and functional impairments have reached a point where specialized end-of-life care is necessary.

Individuals with a FAST score of 7A or higher often require assistance with most, if not all, activities of daily living (ADLs). These activities may include eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, and mobility. Additionally, they may experience communication challenges, memory loss, and an overall decline in cognitive abilities. The FAST score helps healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families make informed decisions regarding the appropriate level of care, including hospice services, to ensure the individual's comfort and well-being.

Medicare, the federal health insurance program in the United States, covers hospice services for eligible beneficiaries. Medicare's Local Coverage Determination (LCD) provides guidelines for determining hospice eligibility based on the specific medical condition, prognosis, and functional status of the individual. For individuals with dementia and neurocognitive disorders, the LCD outlines the criteria that need to be met for hospice coverage.

The LCD typically includes criteria related to cognitive impairment, functional decline, and the overall trajectory of the disease. It may require documentation of a qualifying FAST score, indicating the individual's advanced stage of dementia. Additionally, the LCD may consider other factors such as recurrent infections, declining nutritional status, and overall decline in medical condition. Meeting these criteria ensures that individuals receive the appropriate level of care, focusing on comfort and symptom management.

Dementia is an umbrella term that encompasses several types of neurodegenerative disorders, each with its unique characteristics, underlying causes, and progression patterns. Understanding these different types of dementia is necessary for providing appropriate care and support to individuals affected by the condition. Let's delve into the various types of dementia and their distinct features:

Each type of dementia presents its unique challenges and progression patterns. Understanding the differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective management, and tailored care plans. Healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families must be knowledgeable about these variations to provide the best possible support and enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by dementia. Early diagnosis, appropriate interventions, and compassionate care play vital roles in improving the well-being of those living with dementia and their loved ones.

In the realm of dementia care, hospice services emerge as a beacon of compassion and comfort, providing a sanctuary for individuals navigating the challenging journey of advanced dementia. Hospice care becomes an essential companion during this critical phase, offering specialized support that enhances both the quality of life of patients and the emotional well-being of their loved ones. As individuals with advanced dementia face the formidable decline in cognitive and functional abilities, hospice steps in to offer solace, dignity, and a comprehensive approach to care that is as empathetic as it is effective.

For patients with advanced dementia, hospice services serve as a lifeline, offering tailored care that focuses on pain management, symptom relief, and emotional well-being. Hospice professionals possess a deep understanding of the nuanced needs of individuals in end-stage dementia, providing expert guidance to alleviate discomfort, anxiety, and distress. Through carefully designed interventions, hospice services enhance patients' comfort, fostering an environment of tranquility that nurtures their dignity and humanity. The holistic care approach encompasses not only the physical aspects of care but also addresses the emotional and psychological well-being of both patients and their families.

Loved ones of individuals with end-stage dementia can find solace in the embrace of hospice care, as it offers not only practical support but also a compassionate presence during this profoundly challenging period. Hospice teams work closely with families, helping them navigate the complexities of dementia care, offering respite, education, and emotional guidance. Family members can expect a multidisciplinary team that includes nurses, doctors, social workers, counselors, and volunteers, all dedicated to creating a nurturing environment that preserves the dignity and comfort of the patient. As the progression of dementia can be emotionally demanding for families, hospice also provides much-needed psychological support, helping loved ones cope with grief and make the most of the time they have left with their cherished family member.

In the realm of dementia care, hospice services shine as a beacon of compassion and empathy. Through their expertise, dedication, and unwavering commitment, hospice professionals offer patients with advanced dementia the opportunity to transition with grace, comfort, and respect. Families can expect not only comprehensive care for their loved ones but also a support system that holds their hands through the challenges of end-stage dementia. In the final chapter of the dementia journey, hospice care becomes a testament to the power of human connection and compassion, reminding us that even in the face of decline, every individual's story deserves to be honored and cherished.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.